19 December 2018

Caught in US–China crossfire

Nine days ago, former diplomat Michael Kovrig was picked up by authorities in Beijing and taken to prison, where he has been held without being formally charged or allowed access to lawyers. His crime is his nationality: he is from Canada, a country whose ties to China typically look much like Australia’s. Kovrig’s imprisonment is almost certainly a retaliation against Canada for arresting Meng Wanzhou, a senior executive at Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei. She was passing through Vancouver airport when Canadian customs were alerted to a US warrant to extradite her, for allegedly conspiring to breach its trade sanctions against Iran.

Beijing warned Canada it would face “grave consequences” if Meng was not released. Three days later Kovrig, an analyst at The International Crisis Group, had been detained, along with Michael Spavor, a Canadian entrepreneur who promotes tourism and investment in North Korea. China did not seem to care that extradition treaties prevented Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau from having any control over Meng’s arrest.

Donald Trump further embroiled Canada by explicitly politicising the affair and linking it to his trade war with Beijing, noting that he was willing to intervene in the criminal case against her. “If I think it’s good for what will be certainly the largest trade deal ever made – which is a very important thing – what’s good for national security, I would certainly intervene,” he told Reuters.

The arrests of Kovrig and Spavor show, yet again, that China will avenge perceived slights. Meng is the daughter of Ren Zhengfei, the founder of Huawei. The firm is the world’s largest telecommunications manufacturer but has gained notoriety in recent years after countries such as Australia, the US and New Zealand banned it from projects due to national security concerns.

Beijing barely hid its motivation for arresting the two Canadians. Last Friday, China’s ambassador to Canada, Lu Shaye, went further, warning in a speech in Ottawa that a Canada–China free trade agreement “faces new obstacles due to reasons known to all”.

Meng has been released on bail, with a guarantee of A$10.3 million, and is living in her lavish Vancouver holiday home while she awaits extradition hearings. The two Canadians in China have enjoyed no such due process. Based on previous similar cases involving foreign detainees, Kovrig and Spavor are likely being held in a secret prison where they face sleep deprivation and hours of daily questioning designed to coax a confession.

Their predicament is an unfortunate consequence of their country being caught up in rising tensions between the global superpower, the US, and the contender, China. It was fortunate for Australia that Meng’s holiday house was not in Mosman or Toorak.

China’s hard-line, vengeful approach has been consistent and is unlikely to change. Worryingly, it seems that Washington, particularly under Trump, cannot necessarily be trusted to prevent its friends from becoming caught in its rivalry with Beijing. Indeed, it may sometimes – or often – be in Washington’s interests to see ties between its allies and China deteriorate. Last month, for instance, after Trump met his Argentinian counterpart, Mauricio Macri, in Buenos Aires, the White House released a statement describing their shared concern about China’s “predatory” economic behaviour. Argentina, which relies heavily on Chinese investment, quickly denied that the term “predatory” had been used. It hardly matters whether the White House claim was by error or design: it clearly had little concern about any potential strain on Argentina’s relationship with China.

When caught in the crossfire, countries such as Argentina, Canada and Australia – and countless others – can only attempt to clean up the mess, and to hope for the emergence of less headstrong leaders than Trump or Xi Jinping. The pair have agreed to try to reach a truce in their trade war by March 2019, but there is little sign of a lasting peace. Trump faces re-election in two years. Xi is leader for life.

It’s a Wrap

Happy 2019

And finally, a quick goodbye to 2018. This will be our last AFA Weekly for the year, and we’ll return on 23 January 2019. Thanks for joining each week, even if we might all have sometimes preferred that the events under discussion had not happened.

In April we launched the first AFA Weekly, which looked at Donald Trump’s opening rounds in his trade war with China – and, as this week showed, the fallout continues. Other events and themes that shaped Australia’s world in 2018: Trump’s summit with Kim Jong-un, Xi Jinping’s hard-line rule, concerns about rivalries in the South Pacific, the rise of autocrats, and Japan’s thaw with China and its warmer ties with Australia.

Next year, we will watch closely as Australia and Indonesia go to the polls, as Bougainville considers independence from Papua New Guinea, and as deadlines near for both Brexit and the US–China trade war. I hope these events are decided calmly and wisely, by voters and leaders who treat their decisions with care, reason and empathy. We’ll see.

I look forward to keeping an eye on 2019. Please keep the feedback coming – and if you enjoy AFA Weekly, please share it with those who might enjoy it too.

All the best for the festive season. Happy new year.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prospects for US–China relations in 2019

“American concerns about Chinese state subsidies under the country’s Made in China 2025 strategy will be almost impossible to resolve. The reality is that all countries use degrees of government support for their indigenous technology industries, although China uses the most.” Kevin Rudd, Project Syndicate |

|

How McKinsey has helped raise the stature of authoritarian governments

“While it is not unusual for American corporations to work with China’s state-owned companies, McKinsey’s role has sometimes put it in the middle of deeply troubled deals … In 2015, as China Communications was building the artificial islands and still under World Bank sanctions, McKinsey signed it on as a client, advising it on strategy.” Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe, The New York Times [$] |

|

Policing religion? There’s an app for that

“The [Indonesian Attorney General’s Office] says the app’s main function is to educate the public about deviant religious groups, and to prevent them from following unorthodox teachings. It also provides an outlet for people to report what they deem to be heresy or deviancy, rather than taking the law into their own hands.” Zainal Abidin Bagir, Indonesia at Melbourne |

|

|

|

|

Payne silent on human rights following visit to Myanmar

“Instead of condemning the Myanmar military, we continue to support them, to the tune of around $400,000 a year. We’re one of the only countries that does so. The US, UK, Canada, EU, France and others have cut all ties with the Myanmar military.” Rebecca Barber, Australian Outlook |

|

How WhatsApp fuels fake news and violence in India

“The Indian government has cast much of the blame for these killings on WhatsApp. In August and again in late October, the government asked the company for the ability to stop and trace problematic messages, a demand that would short-circuit the encrypted security that is central to the app’s popularity.” Timothy McLaughlin, Wired [$] |

|

|

Australia’s Foreign Aid Dilemma: Humanitarian Aspirations Confront Democratic Legitimacy, book review by Richard Moore

“One might expect that a country like Australia, almost unique in being rich but located in the midst of developing countries, would be at the forefront of international thinking about economic and social development. Oddly, the contrary is true, as Jack Corbett’s Australia’s Foreign Aid Dilemma reveals.” Richard Moore, HERE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

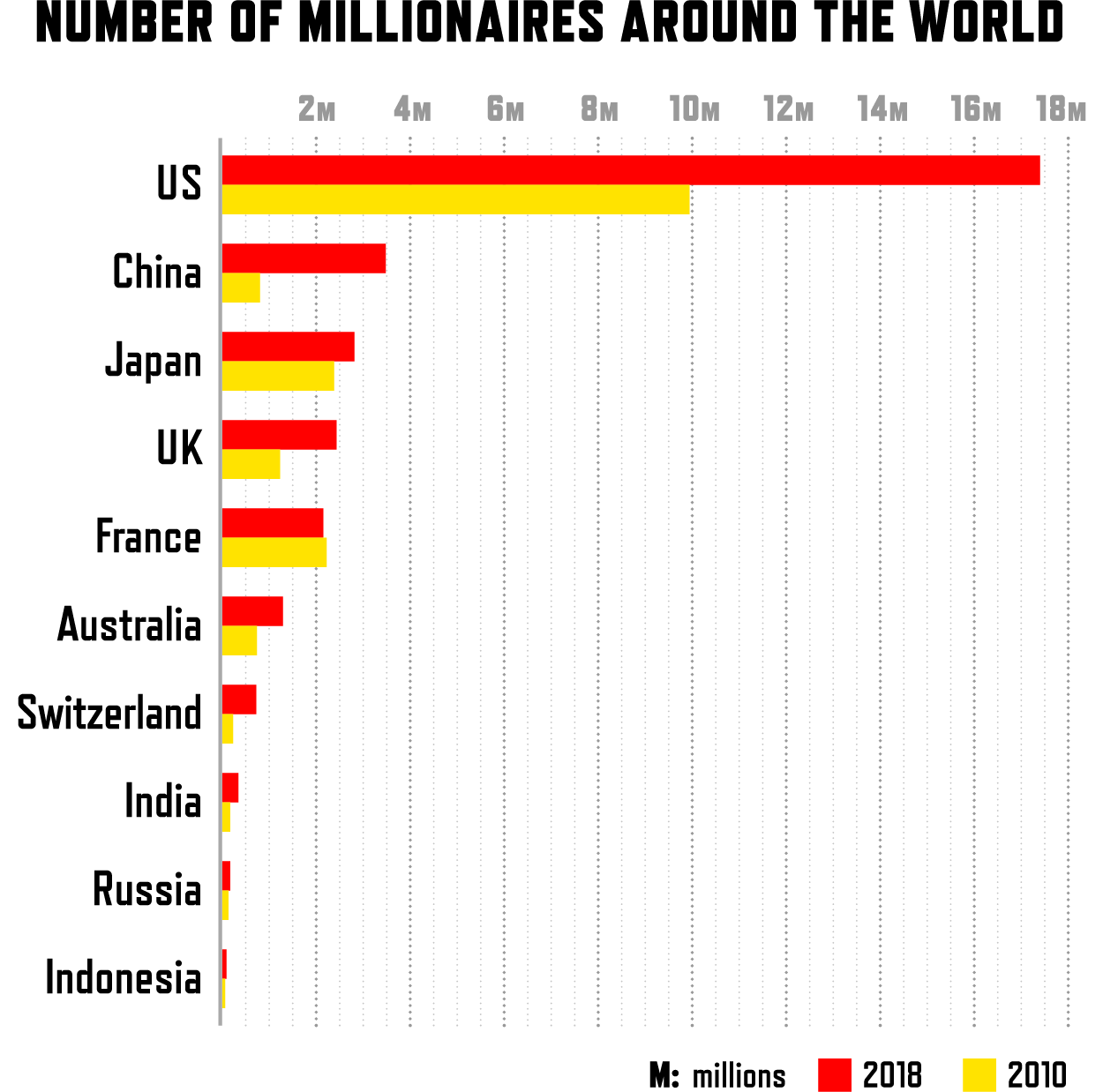

Sources: Credit Suisse Global Wealth Reports 2010, 2018, except for Russia in 2010 (World Wealth Report) and India in 2018 (India Today) |

|