12 September 2018

Trade war fallout

Until last Friday, Donald Trump’s trade war with China had been relatively easy to ignore. Trump’s US$50 billion worth of tariffs on Chinese-produced goods, announced in June, were quickly matched by China, which caused pain to select groups such as vehicle manufacturers and farmers. But the damage could soon spread.

Trump’s plan to impose a further US$200 billion in tariffs prompted Apple to warn on Friday that prices will rise for its computers, watches, adapters and chargers. In response, Trump said on Twitter that Apple should relocate its factories to the United States.

An escalating trade war between the world’s two largest economies will hurt everybody. It is expected to cost Australia AU$36 billion over five years, but this could rise to AU$500 billion over ten years – and result in the loss of 60,000 jobs – if other countries join, according to modelling by accounting firm KPMG.

So far, Trump’s threats – he says he is “ready to go” with further tariffs worth US$267 billion – have affected currencies, including the Australian dollar, but have not caused widespread stock-market jitters. The assumption, despite the weak evidence, seems to be that Trump’s self-destructive tendencies will be checked, either directly or by his advisers.

To encourage a resolution that avoids chaos, countries such as Australia need to understand Trump’s motivations. Yet this is no easy task. Trump seems to have three aims: to address America’s trade deficit with China, to change global trading rules that favour China and to contain China’s transformation into a global power.

The first stems from Trump’s long obsession with trade as a zero-sum game. He believes that the United States is being “taken advantage of” by nations that export more to the USA than they import. This explains his willingness to place tariffs on both competitors and allies, and it is the reason that Australia, which has a AU$20 billion annual trade deficit with the United States (as Malcolm Turnbull regularly reminded Trump), has largely escaped his wrath.

Almost all economists disagree with Trump’s approach on this. His former economic adviser Gary Cohn failed to persuade the president to abandon his tariffs, and so resigned. Canberra, too, has been vocal. Scott Morrison has warned of the dangers of “the new romantics of protectionism”, but there appears to be little that anyone can do to dissuade Trump of a view he has held for decades.

In contrast, the second aim – to revamp trade rules – has strong international support. For years, China was encouraged to join the global world of commerce, and little attention was paid to the ways in which it could exploit the system. But China has now risen. Its theft of intellectual property and its double standards – such as its denunciation of Australian curbs on investments that it would not allow from foreign firms – are more glaring and seem less excusable.

The European Union, Japan and Australia all stridently oppose Trump’s tariffs but share his concerns about China’s unfair trade advantages. “There’s no secret that we think China is a big sinner here,” said the European Union’s trade commissioner, Cecilia Malmström, in December. Morrison, as treasurer, issued similar sentiments without naming China, saying that the World Trade Organization system was “built for a different time”. But reshaping the world’s trading system will depend on international cooperation: a form of problem-solving that Trump appears to despise.

Chinese officials are reportedly more afraid of the international community launching a joint assault on its form of “state capitalism” than of Trump’s tariffs. “These sorts of moves make the Chinese very nervous,” Eswar Prasad, a trade expert at Cornell University, told The Financial Times this week. Morrison, and like-minded partners in Europe and elsewhere, should encourage an international approach, but it should not be punitive. It should aim to create conditions from which China could one day benefit.

The other possible motivation for Trump’s tariffs, containment of China, does not appear to be his main goal, though it may be for some of his officials. Trump has shown little interest in Asia’s changing power balance to date and has willingly alienated countries such as Japan that could conspire to contain China.

Still, Trump is erratic and his foreign policy priorities can quickly shift. Containing China through trade barriers may work, but much of the destruction will be mutually assured. If this is Trump’s aim, a 10 to 25 per cent rise in the cost of the next iPhone – or even looming economic turmoil – will seem to him a small price to pay.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Call for Canberra to pressure China over Muslim detention camps

“The Foreign Minister’s office would not say whether Australia would consider sanctions or use its seat on the Human Rights Council to pressure China on the issue.” Michael Smith, Australian Financial RevieW [$] |

|

North Korea needs a new approach

“The tragedy is that while Trump’s unpredictable, idiosyncratic methods initially proved effective, his policy incoherence has led to an impasse … The opening was not connected to any wider, well-conceived diplomatic process to translate aspirations into results.” Robert A. Manning, Nikkei Asian Review |

|

A would-be city in the Malaysian jungle is caught in a growing rift between China and its neighbours

“Beijing calls it the Belt and Road Initiative. Critics, like Mahathir and others in Asia, call it an attempt by China to become the unchallenged economic big brother in the region and indirectly influence political affairs through its spending.” Shibani Mahtani, Washington Post |

|

|

|

|

The myth of a vegetarian India

“India, whose population is predicted to overtake China’s, is rapidly changing from an agricultural society to an industrial economy with a surging urban population. This is driving the fastest-growing poultry market in the world, as cultural norms change and eating meat becomes a status symbol.” Tani Khara, The Conversation |

|

Biological bounty is the ocean’s richest treasure

“Around 13,000 genetic sequences from more than 800 marine species have been patented — with just under half of all patents belonging to the German chemicals company BASF. These striking statistics will feature in UN discussions … on a contentious issue: who should own and profit from the ocean’s immense biodiversity?” Anjana Ahuja, Financial TimeS [$] |

|

|

Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System, book review by Richard Denniss

“No one is less powerful than someone asking for help. And few politicians prioritise the needs of those who can’t vote. So it should come as no surprise that for the last fifty years little political attention has been dedicated to developing a humane, sustainable and efficient way to deal with the inevitability of refugee crises.” Richard Denniss, HERE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

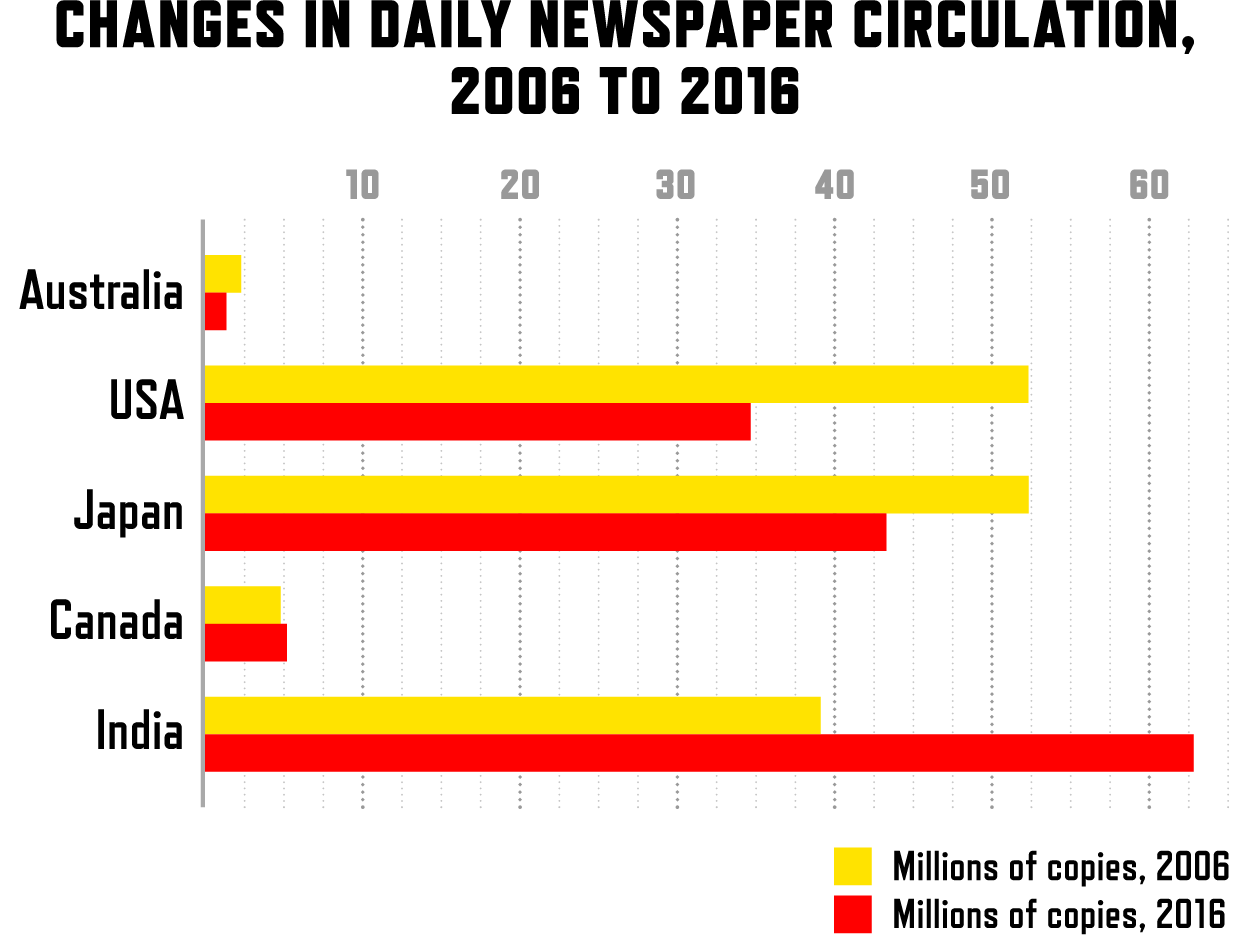

Sources: Mumbrella, 2017; ‘State of the newspaper industry in Australia’, University of Canberra, 2013; Statistica (United States), 2018; Statistica (Japan), 2018; Pressnet, 2018; Nippon, 2005; News Media Canada, 2018; World Economic Forum, 2017. |

|