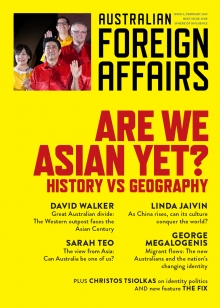

This correspondence is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 5: Are We Asian Yet?.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Intellectual preoccupations come and go. “Transparency and accountability”, once widely recommended, now rarely figure in the discourse. “Globalisation” and “governance” have recently yielded top place as the most overused expressions in foreign affairs to “the international rules-based order”. This latest buzz-phrase – featured in last issue’s Back Page section – is more often cited than applied, particularly by Australian governments. It means different things to different people: to economists it’s the Bretton Woods institutions; to lawyers and diplomats it’s the international legal system, repeated appeals to which count for less and less. Even rationalism, the orderly emblem of the Enlightenment, is being overruled by rules-free Trumpery, Michiko Kakutani argues in The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump. So it’s surprising that Stephan Frühling should refer to another “new world order”, a phrase that was on everyone’s lips in the years of President George H.W. Bush, but that hardly applies to today’s disorderly world.

Equally unexpected is Associate Professor Frühling’s reference to a “nascent debate” about Australia acquiring nuclear weapons. This debate must be taking place quietly inside our proliferating national security establishment, for it is not audible in the wider community. Occasional expressions of enthusiasm are heard from those with vested interests in Australia developing nuclear power plants, but these voices never raise nuclear weapons. If plans exist for our future submarine fleet to be nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed, the government has not taken the risk of revealing them, nor what their eye-watering cost to our “debt and deficit” would be. When Australia’s ICAN won the latest Nobel Peace Prize for its promotion of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, many outside the major parties were delighted. If Australians want nuclear weapons, Frühling’s article is the first many of them will have heard of it.

Frühling’s account of Australia’s on and off, past and prospective, nuclear involvement is useful, if necessarily selective. It is salutary to be reminded that ever-eager Australian defence planners sought to enable the new F-111s to carry nuclear weapons, and that they were again considered for Australia following China’s first atomic test of 1964. But Australians remember vividly the British nuclear tests at Maralinga, whose dreadful consequences Frühling fails to mention. He omits Australia’s efforts over many years to achieve nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament and to eliminate nuclear testing. He does not discuss Canberra’s current bipartisan about-face, refusing to ban atomic weapons, even though it could back his argument that Australia should consider acquiring an independent nuclear capability. He refers repeatedly to Australia having to get American permission to build our own nuclear weapons but does not explain how or when Australia incurred this obligation. Safe reprocessing and disposal of Australia’s nuclear waste he ignores entirely.

Frühling cogently sets out the possible nuclear and conventional threats to Australia and methodically eliminates all of them, apart from speculating about a future powerful Indonesia. Yet he persists in arguing the case for nuclear weapons, which he says could substitute for conventional forces or complement them, and could have small warheads for short-range “tactical” purposes, particularly in “maritime battle”, to safeguard the sea and air approaches to Australia. Would such restraint, and a “spiked moat” around our continent (as Frühling puts it), deter Australia’s neighbours from responding with an arms race and nuclear weapons of their choice? Would Asian nations with which we need closer and deeper relations (as the October 2012 “Australia in the Asian Century” White Paper argued) trust Australia not to aim our nuclear devices at them? It seems unlikely. Moreover, the more countries have them, the greater the risk that nuclear weapons will be used, accidentally or by design.

The main arguments for and against nuclear weapons, which don’t appear in Frühling’s article, are economic, legal, environmental and ethical. Even for a country such as Australia, which has uranium, the costs of developing nuclear power and nuclear weapons from scratch are crippling, economically distorting and not feasible. Any country that has signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty would be in breach if it built or used nuclear weapons, and could face international sanctions. A country that threatens or uses conventional force against another state that is not directly attacking it is in breach of international law, and its leaders could be accused of the war crime of aggression. A country that causes a nuclear attack releases deadly radiation over a wide area, rendering it uninhabitable even for the humans, animals and plants that survive, and a counter-attack compounds the disaster. A country whose leaders can force others to suffer “what they must” – as Frühling cites the ancient Athenians doing to the Melians – should first consider treating others as they wish to be treated.

Frühling is careful not to prescribe nuclear arms for Australia, and instead sets out our strategic options, suggesting that they deserve timely consideration in the context of an unreliable US alliance. Independence has never been more desirable. But before Australians seek security in nuclear weapons, we should remember Ronald Reagan’s wisest words, with which Mikhail Gorbachev agreed: “Nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” Australia should remind others of them at every opportunity.

Alison Broinowski, former Australian diplomat and academic, and vice-president of Honest History and of Australians for War Powers Reform

Read Stephan Frühling’s response here