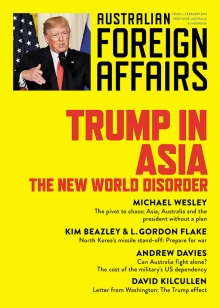

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 2: Trump in Asia.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Two days after Donald Trump was elected, I was having dinner in a Middle Eastern country with an American diplomat – a tough senior Obama political appointee, with hard-fought policy achievements to her name – when she burst into tears mid-conversation. Like the entire commentariat, and virtually everyone in the US political establishment (including, arguably, Hillary Clinton), she had so taken for granted Clinton’s impending elevation that the election hit her like a physical blow. Now she was watching her role in a Clinton administration evaporate; she’d been crying on and off, she said, for days.

She wasn’t the only one. Celebrities (scores of whom promised to move to Canada if Mr Trump won, but later discovered they’d been joking), feminists who regarded Trump’s victory as an assault from a revenant patriarchy and activists who mounted last-ditch legal challenges to deny him the presidency were inconsolable. Bernie Sanders’ supporters were torn between outrage and schadenfreude, claiming their boy could have won if he hadn’t been robbed in the primary. Women marched in nationwide protests alleged to outnumber the inauguration crowd (the real crowd, not President Trump’s imaginary one, which numbered millions, in what his adviser Kellyanne Conway dubbed “alternative fact”). The Resistance – a loose movement viewing Trump as dictator-in-waiting, including factions willing to oppose him “by any means necessary” – was born.

A year after the election, Resistance members, their ranks thinned by the passage of time and Trump’s failure to enact any major part of his agenda, gathered to howl at the moon. I mean this literally: all over the country, people gathered, turned their faces to the evening sky and howled. The president’s manifest ignorance of governing seemed to have found its perfect mirror in an incoherent opposition. Hillary Clinton’s book tour for What Happened, her sorry-not-sorry campaign memoir, drew sellout crowds. Punters coughed up US$600 a head for choreographed events free of any key self-revelation. I’ve never heard of an author charging for a book talk, but this was clearly not really about selling books: these were less literary than expiatory rituals, their grief-stricken attendees simply a more cerebral version of the moon-howlers.

Moral panic, impotent rage and existential despair – call it the “Trump effect,” the 2017 equivalent of 2009’s “Obama derangement syndrome” – was in full flight. Along with the belief that President Trump is a uniquely dangerous fascist, adherents of this view consider his administration a wholly owned subsidiary of the Kremlin, and believe his incompetence (and of course the Resistance) is all that stands between America and the abyss.

A Republican tribal variant – the “Nevertrumpers” – sees the administration as illegitimate, viewing the president (with some justification) as a lifelong Democrat who mounted a hostile takeover of their party, is trashing its principles and is manifestly unfit for office. During the campaign, dozens of Republican defence and foreign-affairs experts, representing their party’s core policy cadre, signed letters disavowing Trump. A few later renounced this thoughtcrime and came crawling back, or expressed astonishment that the White House subsequently turned elsewhere for talent, but most are sitting out the administration in a principled, if somewhat pouting, manner.

I want to offer a different take on the Trump presidency, from the rather oddball perspective of an expat Aussie with no partisan affiliation within US politics, who has lived in America for a decade, and has served as a career official (i.e. not a political appointee) in the Bush State Department and as a consultant to the Obama administration (and who, full disclosure, is very happily married to an Obama political appointee, former Undersecretary of the Navy Dr Janine Davidson). I come neither to bury Trump nor to praise him, but to suggest that his administration, rather than uniquely incompetent or illegitimate, might be an upside-down duck. Let me explain.

I don’t own this metaphor: it belongs to Dr Colin Kahl, one of the smartest foreign-policy professionals in the Obama administration (or, to my knowledge, any other), who was the national security adviser to Vice President Joe Biden and headed the Pentagon’s Middle East portfolio. His image is the best I’ve heard to explain what’s going on. Where President Obama’s administration was once described as the proverbial duck – serene on the surface, paddling like hell underneath – Colin’s view is that the best anyone can hope for is that Trump’s might become an upside-down duck, with sound and fury above the surface, in the president’s tweets and public appearances, but with professionals quietly executing the business of government below the waterline. In this interpretation, the president’s public breaches of decorum would mask a conventional policy program. The administration would be a fairly normal Republican one, just with a stylistically unusual chief executive. I’m not sure I completely buy this interpretation (and neither does Colin), but it’s a useful tool for getting beyond appearances in an administration whose surface has been especially distracting. So let’s run with it for a bit, and see where it takes us.

As Janine has written, most US presidents come into office focusing on domestic issues, with merely a casual interest in foreign policy and defence. As she points out, that’s perfectly understandable, since presidents get elected by a constituency that primarily cares about domestic matters. Still, most new presidents rapidly realise they have little control over domestic policy, and turn their attention overseas by the end of their first term. President Trump is entirely typical of this pattern, though he seems to be following it at a rather accelerated clip. His signature policies (withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement, banning travel from terrorism-affected countries, exiting the Paris climate agreement) all focused externally from the outset – though, characteristically, they were tailored to generate support from interest groups in his base. The failed initiatives of his first year – Obamacare repeal, infrastructure upgrades, creating coal and manufacturing jobs, alleviating the opioid crisis – have, again typically, been largely domestic.

In foreign policy, his actual policy decisions (as distinct from his personal demeanour) have been fairly conventional. His decertification of Iran’s compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, for example, got a lot of criticism, but meant nothing in the international context (certification is an internal US requirement that was imposed on President Obama by Congress against his will, and has no effect on the agreement). Even while decertifying Iran, President Trump didn’t actually withdraw from the deal, no doubt having been advised by his policy team that, as just one of six signatories, pulling out would leave the deal intact but render Washington unable to influence it. Decertification did, however, score points with his base – which, as with most of his other moves, seems to have been the whole point. Again, though, this is largely a matter of style: most if not all presidents find domestic considerations driving their foreign policy. Mr Trump is simply less subtle about it than most.

Likewise, his decision to recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and begin moving the US embassy there from Tel Aviv is less of a departure than it seems (or than the hyperventilation from Democratic or Nevertrump commentators suggests). Trump’s announcement – which amounted to little more than acknowledging the law of the land in the United States since the mid-1990s, and the reality on the ground since the 1960s – was less radical than it appeared and was motivated by a desire to deliver on a promise for a key campaign constituency (evangelical Christians). The difference here is not policy content, but the fact that Trump – charmingly naive as this might seem – is actually following through on a campaign promise.

The policy continuity between the Trump and Obama administrations is notable, but not particularly unusual. All administrations find themselves confronting circumstances they didn’t fully understand on the campaign trail, once read into the classified intelligence sources only available to incumbent governments. Most candidates drop their more inconvenient or impracticable policies once the election is over. Mr Trump has done some of that (the proposed 45 per cent tariff on Chinese imports is an example), but his attempt to keep some commitments, such as the Mexican border wall, suggests he’s unusually attentive to following through on promises, most likely because his extraordinarily low popularity and failure to persuade independents and Democrats means he can ill afford to alienate his base.

Likewise, his strategy on Afghanistan, panned as aggressive war-mongering, was actually quite mainstream in policy terms, though that policy was buried under militaristic bluster. As I watched his speech, I wondered how Biden must feel about Trump stealing his policy from 2009, which was criticised at the time – by Democrats – as too weak. Trump’s plan was almost identical to Biden’s: light-footprint counterterrorism, reliance on drones, the use of air strikes and special forces to suppress terrorists and stop them from attacking the United States, willingness to negotiate with the Taliban, pressure on Pakistan, moving from a withdrawal timeline towards a sustainable footing. The only difference was President Trump’s rhetoric. His plan was basically Biden’s with harsher language – a difference of style, not substance.

Ditto for the “defeat” of Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. Candidate Trump’s bluster about targeting terrorists’ families, carpet-bombing cities and refusing to rule out tactical nuclear weapons drew condemnation. But in office he persisted with Obama-era policies, continuing campaigns against Mosul and Raqqa that Obama started in 2015, interfering little in the decisions of military commanders appointed by his predecessor, and taking credit for developments that were long-planned or outside anyone’s control. His most criticised action – ramping up air strikes, which brought a spike in civilian casualties – echoed President Obama’s massive expansion of the drone campaign, and arguably shortened the conventional phase of the conflict, perhaps even indirectly saving lives.

Speaking of which, far from being defeated, Islamic State is alive and well, with key cadres intact and an expanded footprint outside Syria and Iraq. It has simply (and temporarily) dropped back into guerrilla mode after the failure of its conventional war of manoeuvre, so President Trump now faces the identical problem President Obama confronted before the 2014 ISIS blitzkrieg. Again, other than harsher language and a somewhat shakier grasp of the facts, there’s little to distinguish this president’s approach from his predecessor’s.

On North Korea, again, President Trump is continuing a long-standing US approach – lean on Beijing to control Pyongyang; apply sanctions to discourage the nuclear program; bolster South Korea and Japan with exercises, missile defences and garrisons; and ramp up US missile defences – that goes back (with minor variations) to presidents Obama, Bush and Clinton. This has been failing for twenty-five years, and is as unlikely to succeed in “denuclearising” the Peninsula, especially since North Korea is now a nuclear state with intercontinental ballistic missiles, and there’s no imaginable set of circumstances under which Kim Jong-un’s hereditary dictatorship would give them up. To be sure, President Trump’s insulting rhetoric (“Little Rocket Man,” “short and fat,” “fire and fury”) is something from which previous presidents have shied away. But considering the baroque insults North Korea traditionally hurls at Western leaders, and Trump’s legendarily thin skin, it seems to have had little effect. If anything, his insults may have had a positive impact, if reports of North Korean diplomats wandering the halls of the United Nations in New York, looking to open a back-channel to the administration, are to be believed.

On that note, here’s a radical thought: what if not everything that comes out of the president’s mouth is idiotic by definition? Trump promises a border wall and ridiculously claims he’ll force Mexico to pay for it, and undocumented immigrants crossing the southern border drop to the lowest level since 1971. He boorishly cranks up the rhetoric on North Korea, and the United Nations and China impose unprecedented sanctions on Pyongyang. He heartlessly bans travel from countries with inadequate screening for terror suspects – using an identical list to that proposed in 2015 under Obama – and several make major improvements to their vetting systems. He refuses to endorse Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty until members meet their own funding commitments – outrageous! – and several laggard countries start increasing defence budgets towards the 2 per cent GDP target, something the last two presidents repeatedly asked for but failed to achieve. What if the difference in style not only masks unexpected policy continuity but is actually effective in its own right?

That’s as may be, but – moving beyond the duck metaphor for a moment – the president has also clearly departed from political norms in ways that have hurt his agenda and the country’s reputation. From Australia’s standpoint, these could have significant negative consequences in our own region and beyond.

In effect, the new administration shows a high degree of policy continuity with its predecessors, but a disturbing lack of consistency across its various branches. In our region, this lack of consistency is most apparent – and damaging – in the area of China policy. The Obama administration’s “pivot” (actually, it was called the “rebalance”) to Asia was panned as a purely rhetorical reorientation after a decade of tunnel vision on terrorism in the Middle East, but at least it provided a policy framework for different departments – the Pentagon, the intelligence community, the State Department and aid agencies – to work coherently. In contrast, on issues such as China’s expansive presence in the South China Sea, North Korean nukes, Taiwan, trade policy and regional defence engagement, not only are there multiple competing power centres in the current administration but the president’s position has proven remarkably changeable and contradictory. This has led different agencies to pursue independent, even competing, agendas. It has created confusion and forced allies to further question the future of the American regional security guarantee that has underpinned growth and stability in the region.

In violating norms of politics, most egregious is President Trump’s shaming and bullying of cabinet members, including Jeff Sessions as attorney general and Rex Tillerson at the State Department. Tillerson is alleged to have described the president as a “fucking moron,” one of the few signs of pushback from a secretary of state who has repeatedly clashed with Trump on policy issues and been left humiliated by presidential tweets. No foreign minister can influence other countries unless their leaders believe he has the president’s confidence and speaks with his authority; Tillerson clearly does not. UN ambassador Nikki Haley in New York seems to be running her own foreign policy independent of Tillerson’s – without any intervention from Trump – leaving partners uncertain where exactly policymaking authority lies. For allies such as Australia, that increases the risk of supporting US positions – a fact that clearly underpins the focus on self-reliance in Australia’s recent Foreign Policy White Paper, “Advancing Australia’s Interests.” Trump’s neutering of Tillerson has also contributed to a collapse of morale at the State Department. Combined with the failure to even nominate candidates for hundreds of political appointments in the executive-branch departments, this means that, whatever your view of the president’s agenda, his ability to execute it is increasingly questionable.

Likewise, Trump’s public trashing of Jeff Sessions – one of his earliest supporters – not only undermines Sessions’ reputation, but also makes it harder for the attorney general to advance the president’s agenda with America’s fifty states and 17,000 law-enforcement agencies. President Trump, it seems fair to say, lacks an intuitive grasp of the fact that loyalty goes both ways. Again, this message – and the mercurial disposition it signals – raises costs and risks for allies. The mooted nomination of Admiral Harry Harris, the pro-Australian commander of US Pacific Command, as the next ambassador to Canberra is seen by some in Washington as a means of reassuring Australia of American support. But if the president casually slams his own cabinet members and undermines his own secretary of state, what substantive difference does the president’s choice of ambassador make?

Another norm President Trump has ignored is his violation of the spirit (though not the letter) of an anti-nepotism law enacted after President John F. Kennedy’s appointment of his brother Robert as attorney general. By appointing relatives (including his daughter Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner) as key policy advisers, the president encourages foreign diplomats in the capital to ask a question normally only relevant in third-world autocracies: should we work with appointed officials of the government, or go around them to deal directly with the family? Certain ambassadors – it would be tactless to name them – have become adept at cultivating the Kushners, for example, further disempowering the cabinet and the executive branch, and creating the parallel, informal power structures normally associated with banana republics. Australia can play this game as well as anyone, and better than most – but as a long-standing treaty ally with enduring institutional, economic and cultural ties going back more than a century, we shouldn’t have to.

Politicising the judiciary and law enforcement – starting with the president’s tweet claiming a judge would be unable to render a fair verdict due to his Mexican heritage; continuing with the pardon of Sheriff Joe Arpaio, a famous immigration hardliner; and peaking with his denigration of the FBI and Department of Justice – has been another damaging Trump departure. To be fair, Trump had some solid precedent: President Obama’s use of the IRS to target opponents in the 2012 campaign, Attorney General Loretta Lynch’s tarmac meeting with President Bill Clinton at the height of an investigation into his wife’s illicit email server, and FBI director James Comey’s multiple interferences in the 2016 presidential race are cases in point, along with a string of recent revelations of politicisation within the FBI and the justice department. Again, President Trump seems to be departing from his predecessors’ behaviour not so much in substance, but in lack of subtlety.

One area where the president has departed from recent practice is his selection of numerous military men for cabinet or senior non-cabinet posts. Marine generals James Mattis for Defense and John F. Kelly for Homeland Security, army generals Michael Flynn and H.R. McMaster as successive national security advisors, and General Kelly’s move to White House chief of staff have raised concern about civil control of the military, or militarisation of policy. With the notable exception of Flynn, this concern is tempered by the idea that military officers are the “grown-ups in the room,” an “axis of adults” (to quote Kahl again) restraining the president’s impulses – a role described to me by a friend as “continually trying to stop a toddler from playing in traffic”; Senator Bob Corker, one of the president’s most vocal Republican opponents, called it “adult day care.”

In my view, this makes the prevalence of military officers in the upper reaches of government worse, not better. Far from reinforcing civil control, it puts the highest elected civilian official in the country under the de facto regency of an unelected military elite. Political scientists looking at this set of circumstances in a foreign country would call it a praetorian or “securitocratic” state, which – despite best intentions – is clearly not where the world’s greatest democracy ought to be heading. Again, this is not to critique the officers involved, all of whom I know, and all of whom, I believe, are as conflicted about this as anyone else.

From Australia’s point of view, the officers in key roles are all friends – John Kelly and Jim Mattis, in particular, are very familiar with Australia’s circumstances, positively inclined towards our shared interests, and determined to maintain an effective presence in the region and beyond. But, at some level, that doesn’t make it better – for America’s longest-standing regional ally, institutional and structural connections ought to matter more than the personalities of individuals hired and fired on the whim of a mercurial, startlingly ill-informed president. This comes home most clearly in the issue of nuclear strategy.

President Trump, as commander in chief, is never more than a dozen steps away from the “football,” a briefcase containing a communications system and launch options for a nuclear strike. In the nuclear arena, as in almost no other, the president has virtually unlimited authority, with few checks and balances – especially in the case of response to an incoming nuclear attack, when he might have as few as four minutes to order a launch. Given the president’s escalating tit-for-tat rhetoric with Kim Jong-un, and Kim’s continued missile launches that now seem able to place a nuclear weapon anywhere in the United States (and therefore anywhere in Australia), concern over this recently prompted Congress to review the president’s nuclear launch authorities. From my (admittedly parochial) viewpoint, this suggests a useful rule of thumb: if we feel uncomfortable about President Trump exercising a particular power, perhaps we should ask whether any president ought to have it.

There’s a silver lining to all this, believe it or not. Most presidents bring three kinds of people into office – operatives from their political parties, members of their personal entourages, and their party’s “bench” of policy experts, who normally occupy positions in think tanks or academia while the other party is in power. Hillary Clinton would have been typical in this respect, drawing in thousands of campaign staffers and appointees (such as my tearful diplomat friend) as well as the Democratic Party establishment and a deep policy bench. In the interest of continuity, she also would likely have kept on large numbers of Obama appointees.

Trump, of course, had no campaign structure to speak of, and his policy staff verged on the non-existent, so he had no personal entourage to bring in – other than, of course, his family, which explains their prominence. Likewise, being spurned by the Republican establishment, he had no policy bench to fall back on. And the Republican National Committee bureaucrats he brought in – prominently, Reince Priebus and Sean Spicer – quickly fell victim to conflicts within Trump’s inner circle, driven by political bomb-thrower Steve Bannon, himself ousted after a few months.

The result is that a slew of Democrat policy experts and political operatives, disappointed in their expectations of a job under Hillary, left government. But where they would normally have filled Washington think tank slots vacated by Republicans coming into the administration, they couldn’t – those slots are still occupied, by Nevertrumpers and conservative Republicans whose hatred of Trump rivals the Resistors’. As a result, many of the finest younger leaders in the Democratic Party have moved out of Washington to other cities, breaking the bubble between the capital and the country. Others – more than twenty, at last count – are running in the 2018 midterms or in state and local elections across the country, bringing a much-needed infusion of new blood to their party. Whatever your political orientation, in a system that relies for its stability on two strong competing political parties, this can only be a good thing – especially since, if the 2016 primary battles teach Democrats anything, it should be that their party is in dire need of younger talent and a closer connection to America’s heartland.

One reason many Republican national security experts declined to serve in the administration, beyond personal distaste, was the ongoing stink of collusion with Russia that has hung around the new president and his former campaign staffers. It’s worth pointing out that, more than a year after President Trump’s election, congressional and special counsel investigators are yet to release any evidence of direct collusion. At the same time, US intelligence had already concluded in January that there was a Russian intelligence operation aimed at undermining Hillary Clinton, eroding confidence in the electoral outcome and creating a window of disruption to enable Russia to improve its position in Ukraine, Syria and elsewhere under cover of post-election paralysis. The Russian spooks who organised that operation are almost certainly astounded by how long the disruption has lasted, fuelled by a reflexively anti-Trump media, President Trump’s self-defeatingly thin skin, and the Democrats’ need for a scapegoat after their stunning election defeat. Ironically, the main loser from the Russian influence operation is likely to be Vladimir Putin, who now faces harsher policies on Ukraine, stronger sanctions on his cronies and greater restrictions on his financial interests than he did under President Obama’s de facto appeasement policy.

None of this is to excuse President Trump’s louche, swaggering ignorance, or the Berlusconi-like debasement of American politics that accompanied his election. This debasement is at least as much his opponents’ fault as his own, but barring a catastrophic nuclear exchange (there’s a phrase I never thought I’d have to write) there will be other presidents. This too shall pass, as President Lincoln said. For Australia and other allies, the uncertainties of alliance politics are greater than usual, but then so is the motivation to become more self-reliant, capable and independent in our defence and foreign policy – and that too is a good thing, both for Australia and ultimately for the United States. And anyway, as I’ve argued here, not everything about the Trump administration is bad, or even particularly unusual – it may simply be that the duck, for once, is upside down. •