This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 4: Defending Australia.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Dehjawz-e Hasenzay is a small village in Uruzgan Province, south-central Afghanistan, a dusty mudbrick maze on the dry plains of the largely mountainous region. Late in the evening of 9 July 2006, a seven-vehicle convoy carrying a Quick Reaction Force of Australian commandos rolled into a firestorm to cover the extraction of Canadian special forces from the village. The Canadians had volunteered to be the spear point for a raid targeting Osami Bari, a local Taliban war chief.

Bari was killed in the opening minutes of the fight, cut down as he tried to get off a rocket-propelled grenade shot at the raiders. The mission, to reduce the Taliban’s war-fighting capacity, was successful. A little too successful, really.

Two RAAF Chinooks had dropped the Canadians so close to Bari’s compound that the first man charging down the ramp ran face-first into the wall and knocked himself over. Bari, who routinely travelled with six bodyguards and was thought to have up to 100 fighters he could field on half an hour’s notice, had been attending a war council. An estimated 200 insurgents were in Dehjawz-e Hasenzay that night, and they opened up on the Westerners with a furious torrent of automatic weapons fire and rocket-propelled grenades. The thunder-and-light show was visible from 10 kilometres away, at Uruzgan’s capital, Tarin Kowt.

The Australian commandos fought their way into Dehjawz-e Hasenzay through a rolling ambush by the Talibs and the even more destructive supporting fire of an American AC-130 gunship, which orbited high overhead and raked the insurgents with bullets every time they massed for an assault on the besieged special operators. Racing through darkness resolved into bright green clarity by the long, sinuous lines of the gunship’s tracers, the commandos from the 4th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (4 RAR) fought through to their allies on a scrap of high ground and “circled the wagons” around them, creating a temporary fortress of their vehicles from which the returning Chinooks were able to extract the Canadians. That left the convoy to get themselves out through the warren of narrow alleyways and dead ends, with large numbers of surviving insurgents still swarming them, some firing on the Land Rovers and Bushmasters from within a couple of metres.

The big, all-wheel-drive vehicles punched through the ambush like an armoured fist. They soaked up barrages of small-arms fire, rocket blasts and shrapnel, returning fire with machine guns and grenade launchers. When one of the lighter special reconnaissance vehicles got stuck under fire, forcing its team to dismount and seek shelter behind a crumbling wall, the Bushmaster following behind them parked between the huddled commandos and the Afghani fighters, peppering them with machine guns. The hulking vehicle proved a reliable shield, until the Bushmaster’s grenade launcher and MAG 58 machine gun killed and disabled enough of the enemy to bring about a withdrawal. The convoy finally made it out of the killing ground and onto open terrain, designating one final compound for an airstrike by a waiting B-1 bomber.

The raid on Dehjawz-e Hasenzay, little known back home but reported in detail by Chris Masters in his history of Australia’s special forces in Afghanistan, was a telling example of how a small, technologically advanced force can prevail against a committed enemy with all the advantages of fighting on their own territory, with much greater numbers and even some measure of tactical surprise. The clean lines of communication from ground forces to air support, the importance of night vision and drone coverage, and the brutal simplicity of armour and enhanced lethality all helped to secure victory and minimise casualties.

The Australian Army, along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force, is one of the three armed services that make up the Australian Defence Force (ADF). It has not traditionally conceived of or equipped itself as a heavy, mechanised unit. But at Dehjawz-e Hasenzay in July 2006, we see the outlines of a harder, weightier re-engineered ground force coming into focus.

Since the reforms of the 1980s, masterminded by defence official Paul Dibb, the army has often been seen as the ugly stepchild of the three services. Less reliant on massive injections of capital, more dependent on pure “labour” to achieve its missions, for a long period the army seemed fated to the secondary status of a constabulary force, good for UN-approved peacekeeping gigs or policing threats to far-flung RAAF bases, but little else. Yet as localised as the action at Dehjawz-e Hasenzay was, it did foreshadow deep changes to the strategic conceptions underlying the army’s purpose. In Afghanistan, Australian ground forces projected power, and did so by bringing vastly superior fire power and armoured heft to bear on the enemy.

This shift to power projection is now being realised in the creation of an amphibious force that has few precedents in Australian military history. Australia, alarmed by China’s growing might and the reshaping of the regional power balance, is building a capability that extends beyond its traditional focus on protecting and controlling the continent and its surrounds. It is an ambitious change, fraught with the potential for failure.

Equipping the army: the rise of an amphibious force

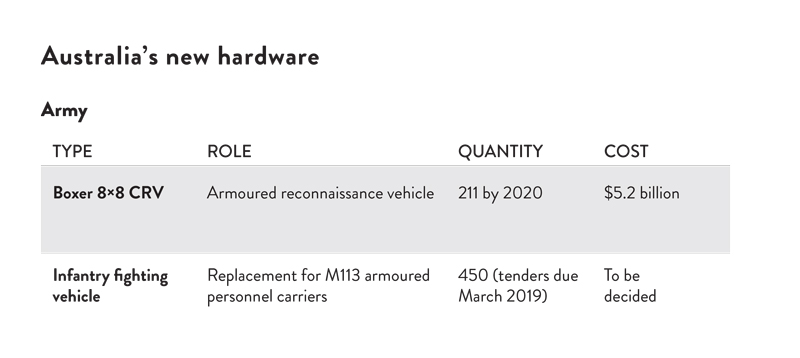

The Australian Army has identified protected mobility as a priority in the face of increasingly sophisticated threats from state and non-state adversaries. Years of roadside bombs, mines, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and insurgent ambushes accelerated the evolution of the Australian Light Armoured Vehicle (ASLAV), a reconnaissance vehicle, into a sturdy, reliable battlefield chariot, but it is coming to the end of its operational life. In March this year, the Queensland-based arm of the German firm Rheinmetall was selected to deliver a new Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (CVR), the Boxer, which will replace the ASLAV. The much larger fleet of Vietnam-era M113 armoured personnel carriers, as decisive at the Battle of Long Tan as the Bushmasters were to escaping the crucible of Dehjawz-e Hasenzay, are now obsolete. In August, the government released a tender for 450 replacement infantry fighting vehicles, plus seventeen support vehicles.

The army’s transformation was mandated by the increasingly lethal and complex environments to which soldiers were deployed after 9/11. The Department of Defence’s 2005 policy update, “The Hardened and Networked Army”, was specifically designed to “increase the size and firepower of the land force, improve the protection provided to our troops, and allow them to communicate better on the future battlefield”. That was thirteen years ago, during some of the fiercest fighting against the various offshoots and franchises of the wars on terror and in Iraq. Since then, the prospects of old-fashioned state-on-state conflict have seemingly increased, in line with China’s growing confidence, strength and assertiveness in both the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Given that the army is the least capital-intensive of the three services, the changes in the organisation’s posture and equipment are the least significant investments Australia will make in national security as a public good. But even so, the cost runs into the tens of billions of dollars. Less visible than large fleets of armoured fighting vehicles, but nonetheless significant, has been increased expenditure on new artillery, an enhanced Austeyr rifle (EF88), body armour and other personal protection systems, soft-skinned transport (unarmoured vehicles), army aviation and C4I (command, control, communications, computer and intelligence) networks. Taken together, these procurement decisions put muscle and sinew on the theoretical framework of the “hardened and networked” army championed by former chief of the army Lieutenant General Peter Leahy.

Boiled down to essences, Leahy envisioned a “combined-arms approach to combat, whereby infantry, armour, artillery, aviation and engineers work together to support and protect each other”. The goal was a more mobile, connected force, deploying with much greater lethality. It was not an entirely radical departure; General Sir John Monash arguably pioneered the approach nearly a century earlier. But a related development, largely imperceptible to the public, yet highly consequential in terms of a strategic rethinking of the army’s role, is the multi-year, probably multi-decade, project to restructure the army as a partially amphibious force, capable of assaulting through and securing a foothold within a contested littoral.

Successive governments have turned the problem of obsolescence across the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) into an opportunity for reinvention. Significant tonnages of the RAN’s new surface fleet have been devoted to moving the heavier, deadlier, networked army around South-East Asia. But questions remain about whether the pivot to amphibious operations is a significant commitment or more of a half-measure.

Expanding the navy: the plan to venture further offshore

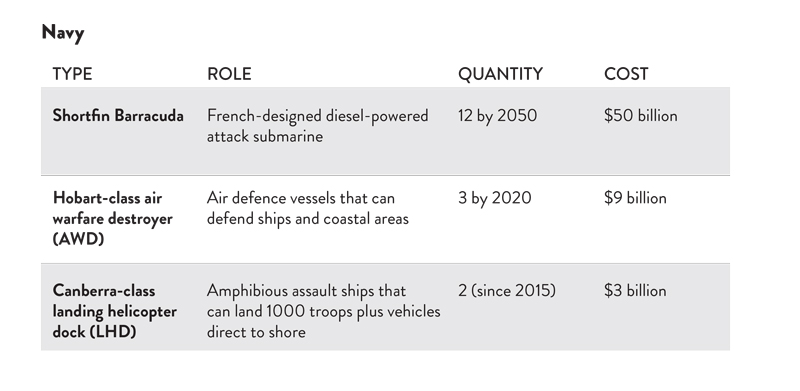

The most visible sign of the ADF’s new outward-reaching ambitions is of course not in the colours of jungle or desert camouflage, but rather in Haze Grey. The RAN’s two Canberra-class landing helicopter docks are amphibious assault ships. Their raison d’être is to deliver a ground force to its objective. In February 2016 that meant loading more than 850 ADF personnel and 50 tonnes of humanitarian supplies to support cyclone relief operations in Fiji. But HMAS Canberra and HMAS Adelaide are warships, and their core function is to transport an amphibious battalion into harm’s way.

The formal origin of the army’s amphibious mission can be traced back to the 2009 Defence White Paper, which worried aloud about ever-increasing Chinese military strength and declining US primacy. But the seed was probably planted during the East Timor crisis, when Canberra was confronted with the challenges of moving thousands of soldiers and their equipment across an uncontested beach. The navy’s shortfall in sealift capacity was exacerbated by delays to the refit of both of its Kanimbla-class heavy transporter ships. The usual drawn-out procurement cycle was sped up, as the government realised it simply did not have the means to respond to a deteriorating strategic environment to the north. The Tasmanian shipmaker Incat was tapped for a two-year lease on the fast, wave-piercing catamaran it had built for a private company to haul ferry traffic across Bass Strait. Incat 045 was commissioned as HMAS Jervis Bay and pressed into service as a fast troop and equipment transport in support of the peacemaking mission to East Timor.

The twin-hulled, blade-bowed cat was a striking sight as it cruised into Dili Harbour with 500 troops and their armoured vehicles, but the ferry was not really fit for this purpose. As the Australian War Memorial records:

A number of sandbagged positions were constructed on the forward deck of the unarmed ship from which machine gunners armed with F89 Minimi Light Support Weapons (LSW) would watch as the ship travelled close to unsecured territory when entering and leaving Dili Harbour.

Two years after the troops’ deployment, 9/11 brought an end to the relative peace of the post–Cold War period and increased the long-term operational demands on the ADF to levels unknown since the Vietnam War. The complexity of the strategic challenges facing policymakers can be traced in the outlines of the military machine successive governments have built in response. Nowhere is this complexity more evident than in the RAN’s expanding fleet list. Facing the likelihood of projecting both land and sea power across the South-East Asian littoral, the unarmed Jervis Bay has given way to the purpose-designed behemoths of Canberra and Adelaide, which together cost about $3 billion. Displacing upward of 27,000 tonnes, the landing helicopter docks’ primary purpose is to deliver a ground force to a location, not to control a sea lane. These amphibious ships offer a wide array of capabilities, ranging through peacekeeping; peace enforcement; contested interventions, where armed opponents resist the arrival of the ADF; stabilisation operations, such as the mission to the Solomon Islands; and high-intensity conflict in the thousands of islands of the Indo-Pacific region. Few to none of these sit within the traditional parameters of the Defence of Australia policy, which was aimed at defending the Australian continent rather than developing capabilities to operate outside Australian shores.

Ever since Paul Dibb and Kim Beazley made a concerted effort to rethink national defence in the 1980s, the strategic guidance that shaped Australian policy and the ADF’s force structure envisioned controlling the air–sea gap between the continent and any potential adversaries. Doctrine, tactics, equipment and training were all directed towards long-range strikes to be carried out by the RAAF and RAN within “the gap”. The Rudd government’s plans to replace and enlarge the submarine fleet – plans now realised in the government’s $50 billion contract with French defence contractor Naval Group (formerly DCNS) to build a dozen 4700-tonne Shortfin Barracuda-class submarines – sits squarely within the model envisioned by Dibb and Beazley. The subs offer only a few limited defence options to policymakers struggling to address potential threats, such as an Islamist takeover of a major Philippine or Indonesian island, but as they’re commissioned they will become major pieces on the chess board in the US Navy’s and China’s manoeuvres for dominance in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

The other major elements of the navy’s build up – three Hobart-class air warfare destroyers (AWDs), which cost $8 billion in total, and the $35 billion contract with British contractor BAE Systems to build nine frigates – sit between the poles represented by the force-projecting landing helicopter docks and the gap-protecting Barracudas. Amphibious operations in a hostile environment expose Canberra and Adelaide to grave threats from many sources. Deploying them anywhere they will be opposed by peer competitors will require layered defences against air, surface and sub-surface threats. The frigates and AWDs would likely supply most of that defence, as the RAAF would be hard-pressed to operate effectively very far beyond the continental shelf.

The navy, of course, is unlikely to warm to the idea of building out a new surface fleet to do anti-piracy patrols, or glorified picket duty. The AWDs and the Type 26 frigates are war-fighters, not security guards. Like the Barracudas, they are strategic assets, deployable to potential battlespaces in the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea. Without its own fixed-wing aircraft, however, the navy is constrained in its ability to offer solutions to the problems of long-range blue-water combat, or amphibious assault.

Air cover is the missing puzzle piece to the ADF’s expeditionary ambitions. Without its own air screen, any Australian force will remain vulnerable to the increasing numbers of fifth-generation war planes throughout the region.

Upgrading the air force: the push for a technological edge

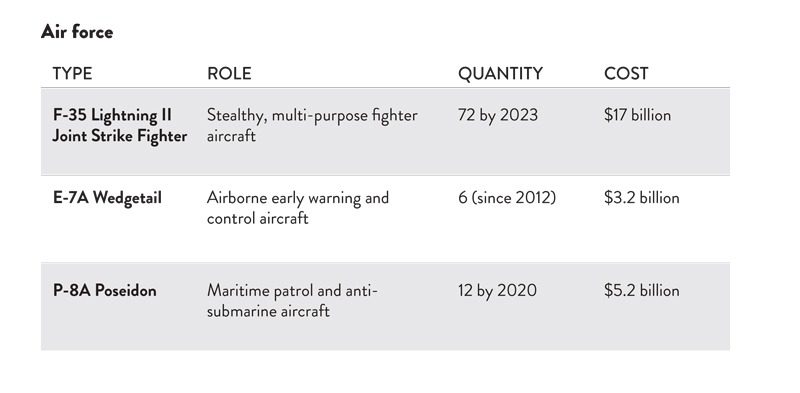

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), like the navy, is a platform-dependent service. The core competency of the air force is air combat, and that will be delivered by our F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters well into mid-century. The seventy-two F-35s, costing a total of $17 billion, are slated to progressively replace the Hornets and Super Hornets, older classes of plane, although it is possible the squadron of F/A-18F Super Hornets might yet be bolstered by more of the same if problems persist with the F-35.

The Super Hornets acquitted themselves well in operations over Iraq and Syria, targeting ISIS ground forces in an operation known as Okra. Actually, more classic-model F/A-18s rotated through Operation Okra than Super Hornets, but because the classics lack the Super Hornet’s longer range, heavier load out (amount of ammunition) and advanced electronic warfare capabilities, they will soon find themselves overmatched by rival aircraft across the region. The unanswered question about the RAAF’s next-generation strike platform is whether the F-35s will deliver. The project has been bedevilled by cost and capability issues since its inception.

The competing cases might be summarised as follows.

The case against the F-35s goes that the aircraft attempts to perform so many roles, and replace so many legacy platforms, that it is doomed to sub-optimal performance in all of them. It is simply not possible to design an aircraft that is best in class at “air-to-air combat, tactical air support, land and maritime strike, advanced tracking and targeting, and electronic warfare”.

The opposing case runs that the F-35 is the iPhone of fifth-generation jet fighters, a stealthy, high-tech weapons system that can take on a multitude of roles once performed by a host of standalone aircraft. Its actual combat power is unknown, and unknowable to anyone without a top-level security clearance.

There is probably a reasonable case to be made for both the prosecution and the defence, but that would not make the F-35 unique. Another of the RAAF’s major acquisitions, the E-7A Wedgetail airborne early warning and control aircraft, spent four years on the defence department’s Projects of Concern list, banished to the procurement naughty corner for schedule slippages and performance issues. The aircraft was released from perdition in late 2012, and by September 2014 was in action over Iraq, managing a complex battlespace. Not only did the aircraft have to track and manage multiple squadrons flown by western alliance partners, but the presence of Syrian and Russian air-force planes conducting their own campaign at cross-purposes to that of the Western allies provided ample opportunities to practise higher-order “deconfliction” – that is, to change the flightpath of a craft or a weapon to reduce the chance of an accidental encounter.

While nowhere near as glamorous or media-friendly as fast movers, the RAAF’s replacement of the old Orion AP-3C maritime patrol aircraft with a mix of P-8A Poseidons and Triton drones will extend Australia’s air cover thousands of miles beyond the borders of the continent, and the half-dozen new Wedgetails (along with twelve EA-18G Growlers) afford the ADF a significant measure of relief from the erosion of Australia’s technological edge in the local region. Focusing on capabilities rather than intentions, numerous regional air forces have been adding to their arsenals – from Indonesia’s upgraded F-16A/Bs and investments in South Korea’s next-gen KF-X fighter program to Malaysia’s Su-30MKM fighters. Not all of them, however, are investing in the systemic enhancement of combat power that comes from investing in battlespace management. Furthermore, simply procuring a weapons platform is not the same thing as managing and sustaining it over a lifetime, a decades-long labour and capital intensive commitment with none of the glamour of welcoming that first shiny fighter that rolls off the assembly line.

Preparing for the next war: the looming defence gaps

Unfortunately, the Asia-Pacific seems fated to endure a generation or more of great power rivalry. Dibb, the first oracle of strategic paradigm shift, recently argued that, given a host of unwelcome developments, both regional and global, “more thought should be given to planning for the expansion of the ADF and its capacity to engage in sustained high-intensity conflict in our own defence – in a way that we haven’t had to consider for several generations”.

The investments in military hardware and technologies over the last ten years have arguably been successful in ensuring the RAN and the RAAF maintain a dominant position over potential regional adversaries. Yet even with the tens of billions of dollars already committed to expanding the ADF, there remain yawning and obvious gaps in capability. The army’s amphibious dreams could quickly turn nightmarish without purpose-designed air cover in a contested littoral. The RAAF has developed and matured proficiencies with inflight refuelling, but Tindal, near Katherine in the Northern Territory, remains a long haul from most of the operational environments into which the navy’s landing helicopter docks could steam. A nation that was serious about amphibious warfare would already have addressed this shortfall, and not by refitting the two existing hulls. Putting a squadron of F-35B short takeoff and vertical landing variant planes into either Canberra or Adelaide would significantly reduce the combat power that the army can embark on the transports. A third landing helicopter dock would help to address the problem, but would not solve it, because maintenance, refit and training schedules all bite deeply into operational availability. If deployed without air cover, the army’s battle groups present exquisitely inviting targets to interdiction from above, given they lack a modern ground-based air defence system. Even non-state actors are developing weaponised drone technology – The Washington Post has reported on US forces coming under attack from ISIS drones in Syria, for example – and this crack in the armour of the hardened and networked army needs to be sealed.

At the strategic level, ballistic missile defence looms as a serious national deficiency. China’s island-building efforts in the South China Sea greatly strengthen its hand in the region. Beijing’s DF-21C/D medium-range and DF-26 intermediate-range missiles are available in both land-attack and anti-ship flavours. From newly constructed bases in the Spratly Island chain the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force can service targets in Singapore and Malaysia and throughout the Indonesian archipelago using the shorter-range 21s. With a reach of up to 4000 kilometres, the DF-26 can punch into northern Australia, delivering over a tonne of conventional or thermonuclear payload to Darwin, and to the Tindal and Curtin air-force bases.

The navy’s air warfare destroyers and Type 26 frigates appear destined to be fitted out with the ballistic missile defence–capable SM-6 missile, but the mostly likely use of these systems will be defence against so-called carrier killers like the DF-21. At some point in the next few years a serious defence minister is going to have to front the cabinet to shake loose enough money for something like an Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defence system for critical civilian and military centres, at least in northern Australia.

Other, less fashionable points of failure within the current force structure can be found in the navy’s inadequate replenishment-at-sea assets, its thin capability to counter mine-laying campaigns and, for the moment anyway, a very real deficit in anti-submarine warfare. The latter will be addressed as the frigates and P-8A Poseidons come online, the latter scheduled to be fully operational by 2021.

But perhaps most critical of all is a vulnerability that is not entirely the ADF’s to defend. Modern Australia’s trillion-dollar economy and complex digital infrastructure is woefully vulnerable to disruption and even destruction without a single trigger being pulled. While the 2016 Defence White Paper engaged thoughtfully with “intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, electronic warfare, space and cyber capabilities”, there really is only so much the military can do on this front.

While in recent years we have witnessed a return to state-on-state competition that would thrill the most jaded of old-school power realists, and this is fuelling Australia’s amphibious ambitions, the greatest national security threat might yet be asymmetric. Modern post-industrial societies draw immense power from their complexity, but that same super-dense interconnectivity is a crucial point of potential weakness, and while it is essential to harden the ADF’s networks against hostile intrusion and disruption by state and non-state actors, this does nothing to protect the infinitely vaster and immeasurably more vulnerable non-military infrastructure, which is more likely to be targeted in the opening micro-seconds of the next war.

There are some basic steps that government, business and private individuals can take to safeguard themselves from low-level cyber intrusions such as May 2017’s WannaCry ransomware attack that seems to have originated in North Korea. Simply installing software update patches as they are released by providers such as Microsoft does go a long way towards securing IT systems. But dozens of states, from the superpowers to middle-ranked actors such as Australia, and even down to rogue criminal organisations, all maintain powerful but unknown capabilities to launch devastating assaults on the digital and real-world infrastructure of chosen targets.