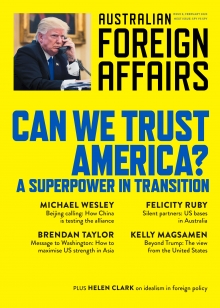

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 8: Can We Trust America?.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Determining the future of US engagement in the Asia-Pacific at times feels like a speculative exercise that revolves around the re-election or defeat of President Donald Trump. But America’s policy in Asia will be shaped by questions that extend far beyond the outcome of the presidential election in November 2020. Many of these questions revolve around China, and the challenge it poses to the interests of the United States and its allies. The nation will need not only to recast its approach to the region but also to make substantial changes at home. How will it adjust to a world in which it is no longer the only dominant global power? And can the region change with it?

Over the last decade, US policies in the Asia-Pacific have each been branded differently – from the “Pivot to Asia” to the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” – but all have recognised the importance of the region to the American economy as well as to the security of its citizens and allies. These policies aim to promote US interests and values, including ensuring the rule of law, enabling freedom of navigation and overflight, broadening economic opportunity and advancing the universal rights of all peoples. This list now also includes managing the relationship with China.

However, America’s ability to advance its regional interests is becoming more contested. No longer does the United States solely dominate the air and sea. China’s massive military modernisation, combined with its assertive territorial and maritime strategy, is challenging the primacy and attendant reliability of the United States. For example, China has steadily advanced its position in the South China Sea while avoiding direct conflict, thereby undermining regional perceptions of American effectiveness and generating friction in US alliances. While the United States will likely be the key military power in the region for years to come due to the overwhelming lead it has in defence spending, its capacity to advance its foreign policy objectives purely through military dominance is increasingly in doubt.

Meanwhile, China’s historic growth over the last two decades has made it the primary economic force in the region. The balance of regional trade vastly favours China – now the largest trading partner of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of key US allies including Australia. The United States – hobbled by its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and its lack of a substitute regional economic vision – has retreated at the precise moment China is surging. Washington’s poorly executed and self-wounding trade war with Beijing, coupled with trade spats with the European Union and key allies such as South Korea, has divided the United States from the very partners it needs to marshal collective economic pressure on China. The result is that US statecraft in the region (and globally) lacks coherence and will ultimately prove ineffective in competing with its chief economic competitor.

At the same time, these security and economic dynamics – the traditional measurements of state power – are being superseded. In this century, the most contested and important domain will be the digital and information arena, where the United States and its democratic allies are already locked in an intense competition with China. The question over which country will dominate 5G technology is likely to be just the first battle in a much longer technology war that will have implications for the global economy, governance, access to information and even military conflict. So far the United States has largely chosen to fight this battle unilaterally, while attempting to line up its friends and allies almost after the fact – Australia being a major exception.

Clearly, we are at a critical point for US policy in the Asia-Pacific. The post–World War II liberal international order is no longer tenable or sufficient to meet the challenges of this century. The order has already been under stress for years, as revisionist powers such as Russia and China have eroded long-accepted rules and norms and promoted an alternative, less liberal vision. Its deterioration is being accelerated by American drift and subsequent questions around US reliability – the result both of Trump and of increasing domestic political dysfunction.

America’s policymakers need to decide on the goals of its policy in the Asia-Pacific and whether it (and its allies) are well positioned to achieve them. The strategy of ensuring US dominance in all domains is outdated, and expensive to pursue; there is also little appetite for it among the American public, which is seeking a more restrained and balanced foreign policy. But it would be strategically unwise for the United States to abandon its efforts in Asia, given the scope of its long-term interests and its deep people-to-people ties. A more realistic approach than chasing primacy or pulling back would be for the United States to aim to ensure that all countries in the region can make their own security and economic choices, free from coercion.

This will require a shift in Washington’s mindset. It will also require sustained and reliable US diplomatic, economic and security engagement and, in some cases, will cause intense competition with China. It will involve more collective and mutually beneficial partnerships with US friends and allies. But chiefly, it will entail the United States being able to present a credible, sustainable alternative to what the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is offering the region and the world.

A plan for Asia begins at home

It may seem counterintuitive, but the strength of American engagement in the Asia-Pacific will depend primarily on decisions about its domestic affairs.

Recent polling by the Center for American Progress showed that the American public lacked even a basic understanding of the goals of US foreign policy. But it also showed that Americans do not want to retreat from a position of global leadership. Instead, there is a strong consensus around making decisions and investments at home that will enable us to lead abroad.

In order for its political and economic model to compete in a contested world, the United States should invest more in its greatest competitive strength: the American people. In competing with China, this will matter as much as – if not more than – what we do in the South China Sea.

Many in the region may fear that a renewed US focus on domestic policy will lead to isolationism and retrenchment. But it is the only way we will be able to sustain US strength. The basic economic and social compact with the American middle class that propelled the United States into the role of global superpower and ensured this position for decades is increasingly at risk. It is time for a new generation of leaders to make the case for the United States’ role not only as a global leader but as a model of the liberal-democratic way of life.

What would investment at home look like? The United States must spend significantly more on research and development in areas such as biotechnology, on public education, on the development of the green economy and on national infrastructure. These aspects are necessary for the country to continue to shape the global economy and provide a credible alternative to China.

And it does not stop at investment. The United States needs to demonstrate to its citizens (and to the world) that it can deliver for its people and solve its most pressing domestic problems. The nation has serious governance challenges: from gun violence to poorly regulated political donations to an increasing lack of fiscal discipline. The political divide between Democrat and Republican is becoming ever wider – and it is unclear how this can be overcome without major political reforms and a new narrative of a unified America.

The United States also needs to make sound choices on where, when and how it chooses to apply its power. After almost two decades of overreliance on the military – from the global War on Terror to the South China Sea – it is time for a major reconsideration of the role that military force plays in US foreign policy. More emphasis needs to be placed on diplomatic, economic, commercial and intelligence tools – and budgets need to better reflect that balance. As of 2017, the United States put 57 per cent of its discretionary spending towards defence. The Department of State, the Department of Commerce and the United States Agency for International Development together accounted for less than 5 per cent of the federal budget. For the first time, there are now more Chinese than American diplomatic posts abroad. And, while important, the US Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development Act – which envisions about US$60 billion in development financing – is a far cry from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. To be truly competitive, the United States needs an extensive and disciplined commercial strategy abroad aligned with its diplomatic objectives – something currently lacking under President Trump and Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross. This would entail far more coordination between the government and the private sector.

Meanwhile, US strategy and resources remain focused on counterterrorism despite erratic efforts across two administrations to address more urgent global challenges, such as China. This is due in part to bureaucratic inertia and a failure to make the necessary investments of time and resources, but also to the absence of a compelling case for a foreign policy that the public can rally behind. For much of the twentieth and early twenty-first century, Americans understood in a visceral way the need to counter the threat from fascism, then communism, then terrorism. The current global context is far more complex and harder to reduce to a simple “ism”. And because the United States and the world are deeply integrated economically with China, it is harder to frame the threat China poses as existential, even if it could end up being so. Although there is a growing consensus in Washington that China will be the main rival of this century, there is not yet the same consensus among the American public.

The good news is that the United States and its people have a unique and demonstrated ability to self-correct. The CCP likes to highlight US political dysfunction to emphasise the relative strengths of its system. But America has seen challenging times before: the Civil War, the Great Depression, the domestic strife over the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement, the 2008 financial crisis and, most recently, the Trump effect. The course correction America needs today requires leadership underpinned by a broader public consensus. That consensus does not yet exist – but US competition with China can, if framed correctly, be channelled to provide the rationale and impetus for change.