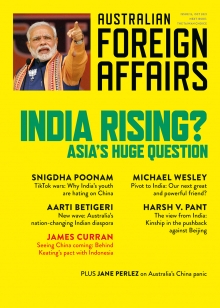

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 13: India Rising?.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

The roots of estrangement

The relationship between Australia and independent India was born troubled. By 1947 Australia had become accustomed to holding a privileged position within the British Empire, as a dominion with a full panoply of prerogatives and expectations. In 1906 Alfred Deakin, Australia’s prime minister, wrote in the London Morning Post that “the British Empire, though united in the whole, is, nevertheless, divided broadly into two parts, one occupied wholly or mainly by a white ruling race, the other occupied by coloured races, who are ruled. Australia and New Zealand are determined to keep their place in the first class.” As India struggled for independence and for recognition of the major contribution it had made to the Empire during two world wars, Australia’s leaders were unsympathetic to its efforts to be granted entry to the small club of privileged dominions. Even after Indian independence in 1947, the inner circle persisted: the white dominions – Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand – made sure that Commonwealth meetings reserved them a space for confidential talks with the British.

Little wonder, then, that there was scant warmth for Australia in India’s new government. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Australia’s prime minister, Robert Menzies, treated each other with icy civility in public; in private, Menzies was as dismissive of India’s stance of non-alignment as Nehru was of Australia’s perceived subordination to the British and the Americans. The White Australia policy established a lasting view of Australia as a racist society, akin to South Africa, in the minds of an Indian elite deeply indignant at the racist condescension of the British Raj. At a personal level, when they met at universities, sporting contests and international meetings, Indians and Australians more often than not rubbed each other the wrong way. Indians found Australians loud, brash and uncultured; Australians found Indians haughty, prickly and judgemental.

Apart from shared membership in the Commonwealth and a mutual love of cricket, there seemed to be little that brought India and Australia together. India’s championing of the Non-Aligned Movement and pan-Asianism, and initial closeness to Mao’s China and Sukarno’s Indonesia, raised Australian fears about being surrounded by militant nationalist independent states leaning towards socialism. India was adamantly opposed to Australia’s approach to Asia, which centred on expanding the American alliance system and fighting expeditionary wars to stop the spread of communism.

Geopolitically, India and Australia also occupied different universes. India had been divided against its will at independence, and within twenty years of self-rule had suffered major attacks from its two most powerful neighbours, Pakistan and China. There was no superpower ally that it could or would turn to for help; its relationship with the Soviet Union from the late 1960s was largely transactional. India continues even today to be beset by internal secessionism and irridentist claims along its major land borders. Its strategic attention is focused northwards, towards its unremittingly hostile neighbours: Pakistan in the west and China in the east. The partnership between Beijing and Islamabad means that India has long faced the German dilemma: the possibility of a two-front war against capable and coordinated enemies.

In almost perfect contrast, Australia is an island with no territorial disputes or significant powerful neighbours. To assuage its central anxiety – that it has too few people to defend such a large landmass – it has formed close alliances with culturally and ideologically congruent major powers. American dominance in the Pacific has freed Australia to concentrate on developing trade and investment links with the booming economies of Pacific Asia, and on building institutions to solidify regional relations and prosperity. Just as India’s strategic gaze has traditionally been to the north, away from Australia, Australia’s gaze was to the north and east, away from India. In the 1980s, when laying out its grand scheme for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, an institution that would unite Australia and Asia in shared security and prosperity, Canberra was adamantly opposed to including India.

Australia discovers its other coast

For most of its post-1788 history, Australia has ignored the Indian Ocean. Unlike the Pacific, the Indian has no major island chains. Its one major littoral economy, India, was a British colony, and once independent, remained closed and inward-looking. Although from the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 Australia became heavily dependent on shipping across the Indian Ocean, there was little cause for anxiety while the British navy maintained it as a British lake. Australian and British ships fought several skirmishes in the Indian Ocean during the world wars, but conflict was never serious enough to elevate its western approaches from the status, in Australia’s strategic imagination, of a geopolitical dead zone.

Instead, Australia was fixated on its Pacific approaches. Its northern and eastern shores were girdled with archipelagoes that could – and did – become forward bases for hostile powers. The Pacific was bordered by major powers, both imperial and Asian. It was the site of incessant battles, and of the world’s first war fought with naval and air forces across thousands of kilometres of ocean and islands. It was here that communism seemed most virulently on the march. And it was the rapid development of the Pacific’s major economies that produced a surge in demand for Australia’s energy, minerals and food at a time when the British economy was turning towards Europe.

If the Pacific was Australia’s source of strategic anxiety, US power and regional institutions were its fount of reassurance. The end of the Cold War saw Canberra invest heavily in both; a deepened alliance would anchor US power more firmly in the Pacific, while strong institutions such as APEC would integrate China into a prosperous, liberal regional order. But the scale of China’s ambitions and the dynamism of the region’s economies soon posed questions about the adequacy of US power and regional institutions, as well as about treating the Pacific as a separate region of development and strategy. Ambitions and appetites overspilled the Pacific, most significantly into Australia’s northwestern oceanic approaches. Canberra quietly jettisoned the Asia-Pacific as its regional imaginary and began to speak of the Indo-Pacific. Then Japanese prime minister Shinzō Abe spoke of the “confluence” of the Indian and Pacific oceans. The United States renamed its Pacific Command the Indo-Pacific Command.

Australia has grappled with how to make sense of its Indian Ocean frontier. Its enthusiastic championing of an Indian Ocean Rim Association has delivered scant results. Its leaders and strategists debate where the Indian Ocean region ends – is it at the Indo-Pakistani border, the Gulf, the east coast of Africa? The one thing all agree on is the pivotal role India will play in securing a favourable order in the Indo-Pacific’s western reaches. What is yet to be seen is what that role will look like.

This is a 1126 word extract of a 4933 word essay by Michael Wesley. Get your copy of AFA13: India Rising? to read the complete piece, along with contributions from Snigdha Poonam, Aarti Betigeri and Harsh V. Pant.