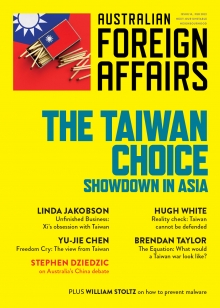

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 14: The Taiwan Choice.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

On 22 May 1995, the Clinton administration announced that President Lee Teng-hui had been granted a visa to give a speech at his alma mater, Cornell University. Beijing was furious. Lee would be the first president from the Republic of China (ROC) – Taiwan’s official name – to set foot on American soil since Washington broke off diplomatic ties with Taipei in 1979 and recognised Beijing as the sole legitimate representative of China. I remember listening to the news in Beijing and wondering what the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) would do, besides merely denouncing the decision, to display its anger. From Beijing’s viewpoint, its “one China” principle was being undermined and if this trend continued, American and regional support for an independent Taiwan would gather momentum.

Beijing’s response came forty-six days later. Xinhua news agency announced that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would conduct missile tests in the waters near Taiwan from 21 to 28 July. Those first tests were followed by more tests, as well as live ammunition exercises and joint PLA naval and air force exercises including highly publicised amphibious assault exercises. Beijing wanted to make it absolutely clear to Washington that the US commitment to a one China policy meant that senior Taiwanese officials were not permitted to visit the United States. Taiwan was not to be allowed space on the international stage.

Tensions between Beijing and Washington soared, especially after US aircraft carrier Nimitz and four escort vessels passed through the Taiwan Strait in December. Three months later, on the eve of the first democratic presidential elections in Taiwan, President Bill Clinton dispatched two aircraft carrier battle groups to the region, sparking fears that the PRC and the United States were on the brink of war.

Fast-forward twenty-six years and one cannot avoid a sense of déjà vu.

The repeated sorties by PLA aircraft into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone (although keeping within international airspace) have served many functions, including trying to intimidate Taiwan and display the PLA’s growing military might. Above all, as in 1995–96, the PLA’s actions today reflect Beijing’s anger and determination to signal that a formal separation between the mainland and Taiwan is unacceptable.

Since taking office a year ago, US president Joe Biden has continued the Trump administration’s policies aimed at normalising Taiwan’s international engagement. Now other countries are following suit. In 1995, PRC officials said to me privately: “If we don’t stop this kind of movement towards a separate Taiwan, we will wake up one day to the US demand that we accept Taiwanese independence.” There is no doubt that the same is being said in Beijing today.

After the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait Crisis, analysts such as Robert Ross delved into the details of the ten-month period of elevated tensions: the governments in Beijing, Taipei and Washington engaged in many types of signalling, to each other and to domestic audiences, and negotiated quietly behind closed doors. Ross concluded that none of the three parties had any intention to go to war. “China used coercive diplomacy to threaten costs until the United States and Taiwan changed their policies,” Ross writes in his 2009 book. “The United States used deterrence diplomacy to communicate both to the Chinese and regional leaders the credibility of its strategic commitments.”

Now, as in 1995–96, no one wants war. Beijing continues to rely on coercive diplomacy and Washington on deterrence diplomacy. However, it would be a mistake to presume that the current fraught cross-Strait situation will be defused as it has been so many times over the past seven decades. Tensions have waxed and waned ever since Chiang Kai-shek and his defeated Nationalist (Kuomintang) troops fled to Taiwan in 1949 after the post–World War II Chinese Civil War and the capital of the Republic of China moved from Nanjing on the mainland to Taipei, Taiwan’s largest city.

Today’s tensions are more precarious than ever because all three parties instrumental to Taiwan’s future – Taiwan, the PRC and the United States – have changed their approach.

What hasn’t changed is the unbending persistence by the PRC that Taiwan is part of China. And that the PLA will use force if necessary to deter Taiwanese independence.

Whether peace can be maintained across the Strait will depend on above all, which path PRC president Xi Jinping takes to achieve unification, which, in his words, is “an inevitable requirement for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people”.

Cross-Strait tensions

Taiwan is becoming more and more repulsed by the authoritarian policies of Xi and less and less inclined to consider a future linked together with the PRC. The United States under Biden has continued the Trump administration’s policy of treating Taiwan as a normal country in new subtle ways, while asserting it still upholds Washington’s commitment to officially recognise only “one China” – the one that the PRC represents. And in Beijing, Xi’s patience is wearing thin. Importantly, the PRC government has become increasingly vexed with actions in support of Taiwan by the United States and others. Beijing is desperate to stop what it sees as creeping efforts that will lead to recognition by the international community of a separate, independent Taiwan.

Several additional factors have changed over the past years. These are severely straining the peace that has prevailed for more than five decades.

First, Xi has explicitly said he is no longer content to patiently wait for unification to materialise “one day” and wants to oversee unification in his lifetime. Before Xi, the Communist Party of China (CPC) grudgingly tolerated the status quo and put unification to one side while trying to win the hearts and minds of the Taiwanese people through lucrative trade, investment and business opportunities. But Xi’s exact words in 2019 were that unification “should not be left to future generations”. This is a direct rebuttal of Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic approach to the Taiwan dilemma. Deng’s tacit acceptance of kicking the can down the road laid the foundation of peace despite repeated pledges by every CPC leader since Deng that unification is paramount.

Second, the PRC has become more assertive in the past few years, alarming policymakers in Washington and across the region. Xi has proven less risk-averse than his predecessors.

Third, the PLA’s modernisation drive undertaken over the last twenty-plus years has shifted the balance of military power in the Taiwan Strait unequivocally to the PRC. Six years ago, the US Office of Naval Intelligence already assessed that the PRC has a technologically advanced and flexible force that (without US intervention) gives Beijing the capability to conduct a military campaign successfully within the first island chain (for instance, to take Taiwan or the Senkaku Islands).

In particular, the PRC has enhanced its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities, which are designed to deny freedom of movement to potential adversaries, especially the United States, and prevent them from intervening in a conflict near the PRC’s coast or from attacking the Chinese mainland. If hostilities erupted, it would be unthinkable for US aircraft carrier Nimitz to breeze through the Taiwan Strait, as it did in 1995.

Fourth, relations between Beijing and Washington have deteriorated markedly in the past few years. The political mood in Washington is strikingly anti-China. In a city where Republicans and Democrats are at loggerheads, the one issue they agree on is that the United States must curb Xi’s ambitions. Xi, in turn, has stirred up domestic nationalists by emphasising the need to “put all our minds and energies in preparing for war and remain on high alert”.

Fifth, the economic interdependence and people-to-people engagement between the PRC and Taiwan continues to deepen despite political tensions. What is often lost in analysis is that Taiwan’s prosperity is heavily dependent on the PRC, and that hundreds of thousands of Taiwanese live permanently in the PRC. Taiwan is extremely reliant on exports to the PRC despite efforts to diversify. In 2020, close to 44 per cent of Taiwan’s exports went to the PRC (including Hong Kong), a 14 per cent increase from 2019. The value of exports was equivalent to about 15 per cent of Taiwan’s GDP in 2020. For comparison, Australia’s exports to the PRC in 2020 were equivalent to 8 per cent of its GDP.

What has further changed in the last decade is the composition of those exports and the PRC’s increasing reliance on sophisticated Taiwanese integrated circuits (ICs), which are used in semiconductor chips and the manufacture of several advanced technologies such as aerospace components and electric vehicles. Every other Taiwanese industry continues to be of secondary importance in PRC–Taiwan trade, despite the Trump administration’s restrictions on selling ICs with American components to the PRC. The PRC is a major exporter of less advanced ICs but needs to import the more sophisticated versions.

The PRC is making concerted efforts to decrease its dependence on imported semiconductors. How this dependence will impact the cross-Strait dynamic is unclear. The PRC wants access to Taiwanese semiconductor technology; on the other hand, a military conflict would disrupt and possibly devastate Taiwan’s high-tech manufacturing capabilities.

This is a 1509 word extract of a 4994 word essay by Linda Jakobson. Get your copy of AFA14: The Taiwan Choice to read the full article, along with contributions from Hugh White, Brendan Taylor and Yu-Jie Chen.