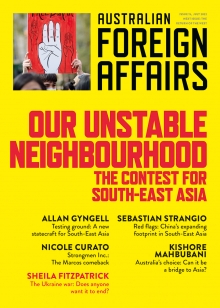

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 15: Our Unstable Neighbourhood.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Australia’s strategic dilemma in the twenty-first century is simple: it can choose to be a bridge between the East and the West in the Asian Century – or the tip of the spear projecting Western power into Asia.

Different Australian governments have pursued each option in recent history. In the 1990s, when I served as the permanent secretary in the Singapore foreign ministry, we worked with Australian leaders, including Prime Minister Paul Keating, Foreign Minister Gareth Evans and Permanent Secretary Michael Costello, to draw Australia closer to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Indeed, we spoke ambitiously of creating a new community of twelve: the ten ASEAN states, Australia and New Zealand. More recently, Scott Morrison’s government has swung in the opposite direction, serving as the tip of US power in Asia and adopting foreign policy positions at great variance with the choices of the ten ASEAN states.

No ASEAN country has joined the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), nor is any likely to do so. But ASEAN has not succumbed to appeasement; it has been treading a careful middle path, neither placating nor antagonising China, while working closely with other powers, including the United States. Australians should ask whether there is some geopolitical wisdom in the choices made by its ASEAN neighbours. And it should consider the consequences if it insists on serving as the spear of Western power in Asia.

After the May 2022 election, the Morrison government is out. With the Albanese government, a golden opportunity has emerged for Australia to undertake a strategic reset. It should grasp this opportunity with both hands.

The Asian Century

Over the past 200 years, Australia has grown and thrived in an era marked by Western domination, first by the British Empire and then by Pax Americana. As a member of this powerful Anglo-Saxon family, close to the global centre of power, Australia enjoyed many privileges. It also enjoyed an enormous sense of security as it was, implicitly or explicitly, defended by great Western powers. And when the USSR collapsed, Australia shared in the West’s joyous triumphalism.

This history explains the overarching Australian refusal or reluctance to accept the most fundamental geopolitical reality of our time: that the era of Western domination is ending. Over the past few decades there has been a massive shift in power. In 1980, in purchasing power parity terms (regarded by many economists as a more accurate way to compare economic weight than using currency market conversions), China’s GNP was 10 per cent of that of the United States. By 2014, China’s GNP had become larger. In market terms, the US economy was eight times the size of China’s in 2000; by 2020, it was only 1.5 times larger. Equally importantly, the United States was the largest trading partner for most countries in the world for many decades after the establishment of the GATT in 1947. In 2000, over 80 per cent of countries traded more with the US than with China, but by 2020 almost 70 per cent (128 countries out of 190) had more trade with China.

In 2022, with the resurgence of trans-Atlantic solidarity following the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine and devastating Western sanctions on the Russian economy, there is a growing perception that a strong and united bloc of Western powers has returned to dominate the world order once again. The vote by 141 out of 193 UN member states to condemn the Russian invasion seemed to show a strategic alignment between the West and “the Rest”. Yet countries that represented more than half the world’s population, including populous nations like China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and South Africa, didn’t vote in favour of the resolution. As a share of the world’s population, 51 per cent abstained, while only 42 per cent approved.

And when the West imposed sanctions on Russia, few non-Western states joined them, with the exceptions of Japan, South Korea and Singapore. Significantly, some key friends of the United States – including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – did not impose sanctions.

Will trans-Atlantic solidarity last after the war in Ukraine is over? Will the rest of the world continue to develop patterns and habits of cooperation outside the Western orbit? Only time will tell.

The best guess one can make is that we will see a new multipolar world order, replacing the bipolar order of the Cold War and the unipolar order of the post–Cold War era. A deep disquiet has developed in key capitals about the weaponising of the US dollar as a geopolitical instrument. Many central banks are troubled that half the assets of the Russian central banks could be seized. Hence, countries will be looking for alternatives to their reliance on the US dollar. Nothing will change right away. But if many large countries seek to carve independent space for themselves, the world will move towards a post-American, post-Western world order.

This is where we find the greatest distance between the ASEAN and Australian perceptions of world order. Australia refuses to accept that it needs to change course. The differences are most apparent in the approach to China.