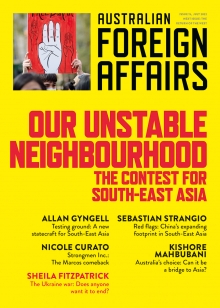

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 15: Our Unstable Neighbourhood.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

South-East Asia is the hyphen in the Indo-Pacific. Shaped by the great river systems of the Mekong, the Irrawaddy and the Salween, the subcontinental bulk of the mainland states of Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos fractures into the archipelagos and islands of Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Indonesia and the Philippines. Linking the Indian and Pacific oceans, the Malacca, Sunda and Lombok straits are critical to the security of China, Japan, the Republic of Korea and, because of its alliance commitments, the United States. Its 650 million people constitute a combined economy of around US$3 trillion.

The region is vital to Australia’s security, too, stretching across its northern approaches and sea lanes, the most likely approach for any military attack.

Over seventy-five years, South-East Asia has tested Australia’s foreign-policy capabilities like no other part of the world. After World War II, it was where the country came to terms with the newly independent states that replaced the departing European colonial powers. A good part of Australia’s diplomatic history in the second half of the twentieth century can be read as a response to the intertwined challenges of decolonisation and modernisation in the region: first the Indonesian independence struggle, then the creation of Malaysia, the Vietnam War, the Cambodian genocide and peace process, and finally the independence of Timor-Leste.

With the creation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967, bringing together Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, then expanding to take in Brunei, the Indochina states and Myanmar, Australia had to learn how to deal effectively with regional institutions.

Over these years, Canberra had larger security stakes in Washington and London. Economically, Japan, South Korea and then China were more important. The ties of language, religion and sport were more significant in the South Pacific. But South-East Asia was where Australia had to learn to manage, mostly on its own, the politics of its neighbourhood.

These were not great powers that needed to be handled warily. Neither were they small states like those of the Pacific, which could be ignored or patronised. Like Australia, they were big enough to have a global outlook and international impact. Their actions had consequences for us.

Although, Thailand apart, they were all emerging from European colonial control, they brought to their statecraft and foreign policies centuries-long experience of responding to and absorbing the clashing interests of dynasties and empires from China in the north and India in the west, from Europe and most recently Japan. All the main religions of the world – Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity and Islam – had passed through and left watermarks of influence.

On balance, Australia handled the challenge well. The management of Indonesia’s attempts to prevent the creation of Malaysia in the 1960s – Konfrontasi (Confrontation) – still stands as an example of best Australian diplomatic practice. Skilfully and alone, Australian leaders sustained high-level relations with Jakarta and the mercurial President Sukarno, while making clear in words and actions their opposition to his policies. The Cambodia peace process under Gareth Evans, Peter Costello’s championing of the US$1-billion Australian contributions to the IMF’s financial stabilisation packages for Thailand and Indonesia during the Asian financial crisis, John Howard’s generous response to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and the careful nurturing over many years of military-to-military ties all benefited our interests and built habits of cooperation.

How Canberra sidelined South-East Asia

South-East Asia is where Australia first learned the difficult lessons of managing intimate relationships with countries and cultures unlike our own. We had to balance our concern with human rights in Suharto’s Indonesia with our interest in stable economic growth and regional peace. We had to weigh our horror at the millions of deaths in the Khmer Rouge’s genocide with the objective of ending further death and conflict in Cambodia.

But over recent years, South-East Asia has become less central to Australian foreign policy. The war on terrorism diverted the attention of our American ally to the Middle East, and Australia followed. Terrorism had an important regional dimension, as the Bali bombings of 2002 showed. It opened new avenues for security and intelligence cooperation. These included the Australian Federal Police’s work with its Indonesian and other regional counterparts, and the Australian Defence Force’s support for counterterrorism operations in the Philippines. But Australia’s primary attention was on Iraq and Afghanistan.

The wars in the Middle East also generated flows of refugees and asylum seekers. Often facilitated by people-smugglers, some of them transited through South-East Asia, looking for Australian sanctuary. Much else, including regional relationships, suffered as the objective of “stopping the boats” became an overriding political imperative in Canberra. “Nope, nope, nope,” was Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s blunt 2015 response to Indonesian and Malaysian pleas for Australia to help resettle Rohingya refugees fleeing persecution in Myanmar.

Then, after the global financial crisis in 2007–08 and Xi Jinping’s elevation to leadership of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, came another reformulation of American interests. Great-power competition, this time with China as the principal antagonist, again became the driver of US strategic policy. South-East Asia became an important arena for this competition.

Over the past five years, as the response to China became the central focus of Australian foreign policy, new priorities – the elevation of the Quad grouping, the defence partnership of AUKUS, and later the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – inevitably distanced it from South-East Asia. The language of Australian foreign policy changed too. The Indo-Pacific replaced the Asia-Pacific.

South-East Asia was not forgotten, but by 2022 it had been sidelined. With the Coalition cuts to the aid budget after 2014 and then a refocusing of the development assistance program on the South Pacific in an effort to preserve “our patch” from Chinese influence, Australian aid to South-East Asia declined sharply.

Despite a raft of trade agreements and the negotiation of the fifteen-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement under ASEAN leadership, Australian trade with South-East Asian countries was sluggish, growing more slowly in the five years to 2019–20 than its trade with the European Union or the countries of APEC. Singapore (at number ten) is the only ASEAN economy to rank in Australia’s top twenty destinations for overseas investment.

And while Australia has been distracted from South-East Asia, it has also become relatively less important to it. That’s partly the result of the region’s economic growth. In the early 1990s, Australian ministers would regularly remind their American and European colleagues that the Australian economy was larger than all the ASEAN countries combined. It is now just under one-third the size. And as the theatre of global strategic competition shifts to the Indo-Pacific, the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, India and the EU have all become more actively engaged in the battle to influence South-East Asia.

The result of these developments is that the region today feels less familiar to many Australians (apart from the 1.2 million or so South-East Asian Australians) than it did in the 1960s and ’70s. The experiences of the Japanese and Vietnamese wars are fading from memory. The excitement of a period of discovery and fresh engagement with new neighbours has passed. The careers of an earlier generation of Australian journalists such as Denis Warner, Barry Wain and Graeme Dobell, who spent years living in South-East Asia and interpreting it for Australian readers, are unsustainable in the tough new media environment. Private philanthropy now supports the Australian Financial Review’s South-East Asia bureau.