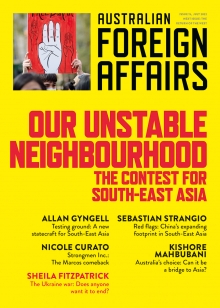

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 15: Our Unstable Neighbourhood.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Every day the news shows us more pictures of apartment buildings crumbling under bombing, streets empty but for some burned-out cars and uncollected bodies, weeping women and child refugees. First it was Kyiv, then the grisly aftermath in Bucha. Then, in scenes of extraordinary devastation persisting week after week, it was Mariupol, a city that had already been pounded in the 2014 war between Ukraine and the Russia-backed separatists of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics.

Every day we see President Zelenskyy personifying Ukrainian resistance and resilience in khaki fatigues. To almost universal surprise, his performance, and that of his country, has been brilliant since the start of the Russian invasion In the course of the war, his first name has morphed in the Western media from Russian Vladimir to Ukrainian Volodymyr, while his last name is making the same shift, from Zelensky to Zelenskyy. His attitude to the Russians has changed too. In mid-March, he indicated that he was prepared to drop Ukraine’s application to join NATO (Russia’s main demand during the lead-up to the invasion) and possibly make concessions on the breakaway regions of Eastern Ukraine. But that was when Ukraine’s speedy military defeat was regarded as inevitable. Later his rhetoric hardened, with promises to fight to the end and talk of Ukrainian victory.

A supporting cast of European and American politicians shed tears of sympathy and offered secondary support (arms for Ukraine, sanctions for Russia, welcome to refugees) while staying on the sidelines. Politicians, including our own, expressed a moral outrage that is widely shared by the public, exhorting Vladimir Putin to “just stop” his invasion. But no leader who has led his nation into war can “just stop”, even if he wants to (and there is no indication that Putin does). They need a way of getting out with dignity and something that can be presented to a home audience as victory, and finding that way often requires behind-the-scenes mediation. There is no sign of anything like that happening at the moment. Europe and the Anglophone world (“the West”) appear united in their desire to punish Russia, but there seems to be no similar resolve about trying to end the war.

Sanctions have not crippled Russia, as some hoped. Putin is not about to be overthrown by an indignant citizenry at home, nor does a coup from within the inner circle appear likely. The Russian army, to be sure, has performed remarkably badly, and one must assume that the same was true of Russian foreign intelligence in the lead-up to the war.

We don’t know for certain what Putin’s real original aim was – preventing the expansion of NATO on its borders, solidifying the breakaway republics’ claim to sovereignty, or guaranteeing a subservient regime in Ukraine – but, in any case, that aim has probably since changed. It cannot have been part of the original intention to focus the attack on Kyiv, with a highly visible convoy proceeding at a snail’s pace along major highways towards the capital; bomb the city and its surroundings; and then pull back (leaving an array of war atrocities for reporters to photograph after their departure), before announcing that Russia would now shift its military focus to the Donbas. In mid-April, Rustam Minnekaev – the equivalent of a US two-star general, who is acting military commander of Russia’s Central Military district, far from the Ukrainian fighting – threw out a teaser with his comments that Russian aims were full control of the Donbas and southern Russia to secure a land corridor along the Sea of Azov to the Crimea. He added for good measure that there was also the possibility of coming to the aid of Transnistria, the Russia-supported breakaway region of Moldova, another former Soviet republic, now independent. But there has been no authoritative confirmation of the first aim, and the Transnistria issue – prompting alarm that Putin’s aggressive intentions go far beyond Ukraine – has not resurfaced.

A brief excursion into history

Western press coverage of the war tends to present a tension going back centuries between two bordering countries, Russia and Ukraine, the former being the historic bully of the latter. This projects a modern notion of nation into the past. Until the early twentieth century, “Ukraine” was an idea circulating in the intelligentsia rather than a political reality. With the collapse of the Tsarist regime in March (by our calendar) 1917, Russia’s newly established Provisional Government recognised the emergence of a small Kyiv-based independent Ukrainian state. But that proto-state failed to thrive, like its Russian sponsor, which was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in November. During the three years of Civil War and foreign intervention in the former Russian empire that followed, a variety of armies captured Kyiv and installed regimes, ending with the one established by the Russia-based Bolsheviks and their Red Army. Not all of what is now called “Ukraine” was part of this state. The Western Ukrainian regions, including Lviv, had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before World War I and went to Poland in the postwar settlement, the victorious Western Allies proving unsympathetic to Ukrainian national claims.

The Bolsheviks – somewhat unexpectedly, given their theoretical rejection of the notion of nationality, as opposed to class, as the vehicle of liberation – were more (though not wholly) sympathetic, and established a Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic as part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1924 (along with the Russian Federation, Belorussia and a Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, later broken up into the three Soviet republics of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan). In the 1920s, the Bolsheviks pushed indigenisation (use of vernacular language in state administration, affirmative action on behalf of non-Russian nationalities in the bureaucracy and education system) in Ukraine, as elsewhere in the union. There was local resentment of the fact that the Moscow-appointed communist leader (Lazar Kaganovich) was ethnically Jewish, not Ukrainian, and recurrent fears in Moscow that the Ukrainian intelligentsia’s brand of nationalism was “bourgeois” (bad, potentially separatist, looking to the West) rather than “Soviet”, Nevertheless, in Moscow’s ambitious first five-year plan, introduced at the end of the 1920s, Ukrainian lobbying for heavy industrial investment often prevailed over its main competitor, the Russian Urals; and the construction of the Azovstal iron and steel plant in Mariupol (then called Zhdanov, after one of Stalin’s closest associates) was one of the plan’s proudest achievements.

Holodomor, the Ukrainian word for the famine that struck the Soviet Union’s main grain-growing regions (Ukraine, Kazakhstan, southern Russia) in 1932–33 as a result of Stalinist collectivisation, was read by many in Ukraine as evidence of Stalin’s malice specifically towards Ukrainians, and it would later become a national identity marker of post-Soviet Ukraine. By the 1930s, Moscow was generally appointing ethnic Ukrainian communists to run Ukraine – but that meant that it was ethnic leaders who, along with a large part of all Soviet republican and regional elites – perished conspicuously in the Great Purge at the end of the decade.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 brought Western Ukraine into the Soviet Union. The whole area was overrun by German occupying forces in the Second World War. But at the end of the war, the Soviet Union emerged with its second-largest republic, Ukraine, significantly expanded by the addition of the formerly Polish western provinces, whose population were not generally well disposed to Soviet citizenship.

Ukraine did well economically and politically under Stalin’s successors, Nikita Khrushchev (himself Ukrainian-born, although ethnically Russian) and Leonid Brezhnev. There was a Ukrainian nationalist wing of the “dissident” movement that developed within the Soviet intelligentsia in the 1970s and ’80s, but, although much publicised in the West, it did not constitute a major threat to the Soviet regime.

Ukrainian nationalism grew during the political carnival of Mikhail Gorbachev’s ill-fated reform effort in the late 1980s, but less dramatically than in the Baltic states (1940s acquisitions, like Western Ukraine) and Georgia. Accordingly, Ukraine was not among the Soviet republics most actively heading for the exit in 1990–91. As late as March 1991, 70 per cent of the Ukrainian republic’s population voted in favour of the maintenance of a “renewed” Soviet Union of “equal sovereign republics”. By the end of the year, however, it had become clear that the union was falling apart, and the Russian republic’s newly elected president, Boris Yeltsin, led the (communist) leaders of Ukraine and Belorussia in delivering the coup de grace, taking their three Slavic republics into independent sovereignty and leaving Gorbachev – still president of the Soviet Union – presiding over an empty shell. This was already virtually a fait accompli when, a few weeks earlier, a second referendum in Ukraine had produced a popular vote of 90 per cent in favour of independence.