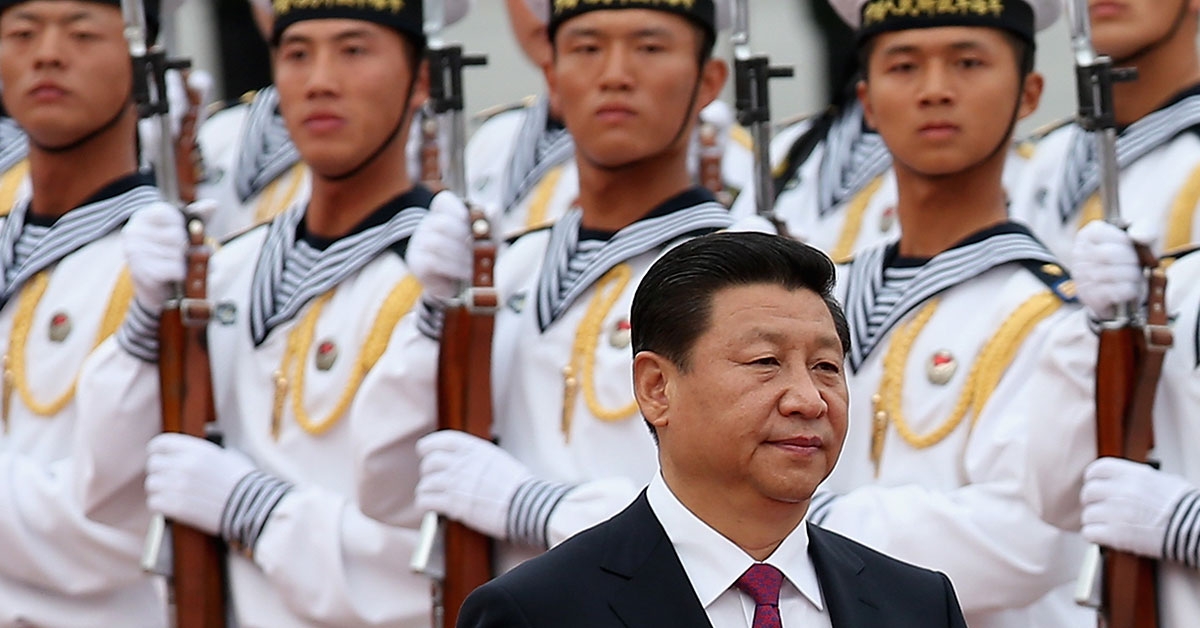

Central to the story of the deterioration in Australia–China relations has been the rise of Xi Jinping. China’s supreme leader is also its most autocratic since Mao, and exceptionally sensitive to criticism – as the considerable number of his imprisoned critics in China can attest. Xi’s harshest critics within (or recently evicted from) the Party may be right when they say that 70 per cent of China’s 92 million Party members oppose his leadership. They may be wrong; it’s impossible to say. As for the other 1.4 billion Chinese citizens: who knows? The PRC doesn’t do independent polling. The fact that it spends more on maintaining domestic “stability” through policing and surveillance than on defence says something about the balance of coercion and co-optation.

The Xi era, China historian Geremie Barmé has written, combines “the vitriol, hysteria and violent intent” of the Mao era with “the forensic detail afforded by digital surveillance”. Xi has ruthlessly dispatched factional enemies and rivals under the credible cover of his anti-corruption campaign, crushed China’s nascent civil society and stomped out dissent, while expanding both censorship and demands for ideological conformity. He doesn’t care what the world thinks about what he is doing in Xinjiang and Tibet, or on the issue of Taiwan; he does, however, care what it says.