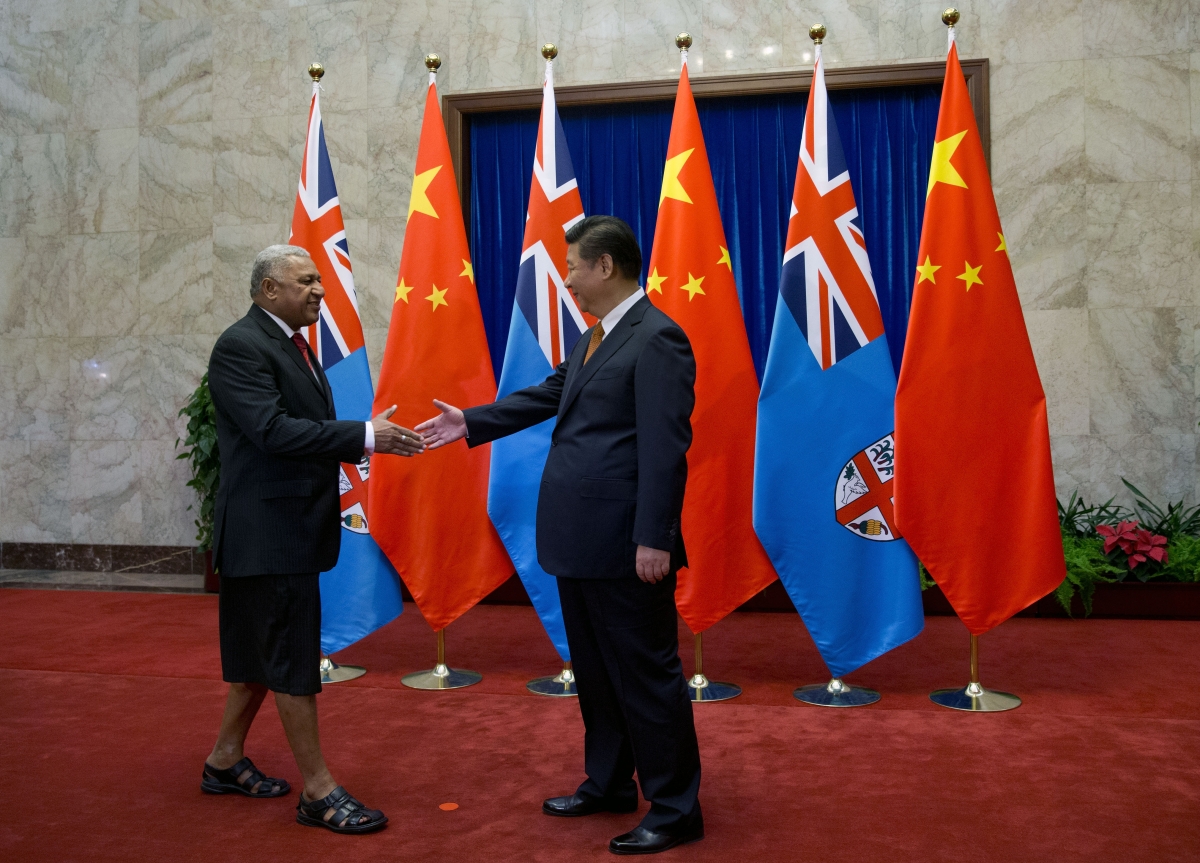

Like empires past, Xi Jinping’s China seeks three grand prizes in the Pacific: wealth, control and presence. Australia and other Pacific nations took time to recognise the nature and scope of this neocolonial ambition and the risk it brings. Responses have veered from complacency to overreaction, fatalism to alarm. The events of 2022 – especially the controversy over China’s security agreement with Solomon Islands – have thus been a useful wake-up call. Australian interests would be directly jeopardised if China were to establish a military base so close to our shores. But even absent that scenario, the prospect of a Pacific island government turning to the guns and truncheons of a one-party nationalist megastate to suppress domestic dissent is confronting.

A long contest has begun. The aim cannot be to exclude one of the world’s greatest powers from the largest ocean. That is neither a realistic strategy nor what most of the region’s governments and peoples want. Instead, the challenge for Pacific island states and their international friends is to craft an inclusive vision for long-term development and protection of sovereignty. The good news is that Australia is far from alone in wanting to build the resilience of the Pacific against China’s control. The Biden administration is expanding American civilian support for the region. But the United States is hardly the only other option. New Zealand, Japan, France, the EU, Britain and India all have much to offer, and others such as Canada, Germany and South Korea could play a part. Taiwan, too, remains a Pacific contributor. China has a rightful place in the Pacific, just not the right to dominate. If many partners sustain their commitment, then all Pacific nations will benefit and strategic rivalry need not permanently shadow the future of the blue continent.

False calm

In 1520, Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan named the world’s largest ocean for the peaceful waters he saw. The name has since become evocative of another longed-for vista: a tranquillity among nations, a place without war. This resonates with the region’s deep cultures of respect and sustainability. Yet there is another side to the character of the Pacific Ocean, with its awe-inspiring scale, life-giving treasures and hidden tremors. The Pacific has been no stranger to the clash of interests among nations.

European colonial empires once competed here for territory and aggrandisement, through exploration, exploitation and worse. America and Australia joined the race in the nineteenth century. In the 1940s, some of the most brutal battles of World War II shattered the calm of its waters, beaches and forests. These thwarted the bid by a militaristic Japan to build a Pacific empire, and heralded America’s own hegemony. The Cold War spared the Pacific as a battleground but not as a testing ground, from the shock and defilement of US, British and French nuclear detonations to China’s first long-range missile test near Vanuatu in 1980. The Soviet Union, then Russia, and for a time even Gaddafi’s Libya sought to embroil Pacific nations in their own schemes. Even in the late twentieth century, as the waves of decolonisation unfurled and thoughts of world war temporarily ebbed, the interests of powerful states were never far from the surface.