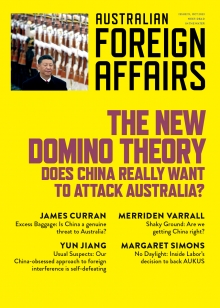

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 19: The New Domino Theory.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Tell the story baldly, and it is beyond belief. Over thirty-six hours in September 2021, not only did the Australian government announce a big change of tack on Australian defence policy, betraying the trust of one ally and further enmeshing the nation with the United States and Britain, but the alternative government backed the move after just a two-hour briefing.

AUKUS, the trilateral security pact with the United States and the United Kingdom under which Australia will become one of only seven countries with nuclear-powered submarines, became bipartisan policy literally overnight. Or that is what the messy first draft of history – the media’s reporting of these events – suggests.

The truth is more complex, nuanced, contingent and contextual. There is a prehistory to AUKUS and how, despite many questions and concerns which have been only partly addressed in the public conversation, it gained the backing of two Australian governments.

In this prehistory, the submarines are not the only, and not the most consequential element. The driving force is a recognition that the United States has lost its technological primacy over China – that it is no longer clear that it can win either a hot or a cold war. In short, the US needs its allies. Donald Trump talked about them having to pay their way. The Biden administration’s language is less transactional, but the message is the same. They are expected to step up.

Meanwhile, in Australia, there has been a slow building of consensus, the origins of which go back almost twenty years and are embedded within the security establishment in all three AUKUS nations. Depending on your point of view, this has led the Labor left to sell out on its historical opposition to all things nuclear and its advocacy of a more independent foreign policy. Or, to take another view – the view of Labor’s parliamentary leadership team – it has made a necessary adjustment to a changed world, in which many superficially contradictory things are true at once. In this worldview, independence, national sovereignty and even peace can only be safeguarded by a tighter, more militarised alliance.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison, whose government had been cooking the AUKUS deal in secret for almost two years, briefed the Labor leadership team on 14 September 2021, ahead of the public announcement on 15 September.

Later that day, there was an emergency Shadow Cabinet meeting. AUKUS was the only topic of discussion. Questions were asked, and the discussion was lengthy and contentious, sources say. But the prevailing mood was awareness that an election was less than nine months away and Labor was on track to win.

“A clear decision had been made . . . that Labor could win the election if it made Scott Morrison the key issue. But it could not allow itself to be drawn or diverted into any other side journey . . . we could not give Scott Morrison anything he could use.” Key to this was the memory of the 2019 election and how a scare campaign about Labor’s tax and spending policies had led to an unexpected defeat. And so Shadow Cabinet ticked off on AUKUS.

Caucus was not asked to endorse the decision of Shadow Cabinet. It was merely being informed

The next day, news of the AUKUS agreement had leaked to the media. That meant members of the Labor caucus had about two hours in which to prepare questions for the leadership team, before they were called together.

Kim Carr, the longest-serving member of the Australian Senate and a former minister and shadow minister, spoke first, followed by about eight others. He recalls that the concerns raised were “entirely predictable” and included the cost, whether the subs would lead to nuclear proliferation and whether Australia would retain control over how they were used. Carr rubbished the idea that the submarines could be operated without a domestic nuclear industry, even though Albanese had ruled that out as a condition of Labor’s support.

But caucus was not asked to endorse the decision of Shadow Cabinet. It was merely being informed.

The Morrison government had successfully kept the development of the AUKUS agreement confidential. Even close observers had no hint of what was coming, although news of increasing concerns about the French submarine contract was circulating. But some people on both sides of politics were less surprised than others.

Ross Babbage is the CEO of the Strategic Forum think tank, whose goal is to foster “thought on Australia’s security challenges”, including through hosting off-the-record and closed workshops, “generally in partnership with relevant senior officials”, according to the organisation’s website. Babbage has been a regular in the corridors of Parliament House and ministerial offices for many years.

In late 2011 and in May 2012 – four years before the Turnbull government negotiated the agreement with the French to build twelve conventionally powered submarines – Babbage wrote a couple of extraordinarily prescient articles for The Diplomat. He argued that the best submarines for Australia would be nuclear-powered Virginia-class boats, leased or bought second-hand. “It would be sensible to have discussions with both the U.S. and U.K. governments,” he wrote. And, if Virginia-class boats were chosen, they would operate “in very close cooperation with U.S. boats in Pacific and Indian Ocean waters. There are likely to be substantial advantages flowing to both countries from joint basing, logistic support, training and many other aspects.”

In his second piece, Babbage said “this would herald a new level of operational partnership with the United States and substantially strengthen Australia’s contribution to allied operations in the Western Pacific. Canberra’s diplomatic clout in Washington and across the Asia-Pacific would be greatly enhanced.”

Interviewed for this article, Babbage says he had no advance notice of the AUKUS announcement – the secret was indeed tightly held. But nor did it entirely surprise him, because since he’d written those articles, he had been talking to the Americans informally and knew that they were open to the possibility of sharing nuclear submarine technology with Australia.

Babbage says that eight years ago he made “informal inquiries” of people in the United States about selling or leasing nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, and he got three waves of response over about twelve months, with the last from a source in the White House. The message was: “If you really want to be serious let’s sit down and negotiate the best arrangement. But in principle, we’re prepared to contemplate it.”

In Babbage’s view, a decade ago many in Labor were instinctively against the idea of nuclear-powered submarines. Those who were open to the idea didn’t think it was urgent or necessary to have what would inevitably be a contentious debate within the party. But, he says, that has changed in the last five years, due in part to “a series of members of the parliamentary Labor Party who’ve had classified briefings, and a broader range of people who’ve actually done some homework on the deteriorating security situation in East Asia . . . And they realised pretty quickly that the circumstances we now face have changed and are continuing to change quite rapidly.” They concluded, he says, that conventional submarines were unlikely to meet the challenge of the next few decades.

So why has AUKUS had such strenuous pushback from former Labor government ministers, most notably Paul Keating? And what is it that changed the view of their successors in the Labor leadership?

This is an extract from an essay published in AFA19 – The New Domino Theory.