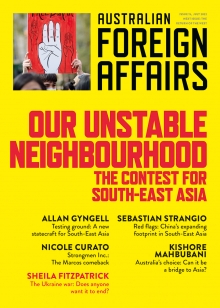

This article is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 15: Our Unstable Neighbourhood.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

Thom Woodroofe on Why Australia Should Host the UN Climate Conference in 2025

“The biggest opportunity for Australia is to use the COP to reinvent its approach to climate change, at home and abroad.”

THE PROBLEM: The Albanese government inherited an Australian reputation on climate change which is in tatters around the world. In the last decade, we have gone from being perceived as a leader to a laggard. While both sides of politics are now committed to net zero emissions, neither has outlined a short-term pathway to reduce emissions that is consistent with our biggest friends and allies or that will keep global temperature increases within 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Australia’s recent stance has had consequences for climate-related threats at home, as well as for our geopolitical circumstances. In the last year alone, we’ve experienced unprecedented floods; the United States singled out climate change as a point of contention in its relationship with the Morrison government; and Solomon Islands struck up a security relationship with China after years of disappointment with Australia – principally about our inaction on climate change.

The perennial refrain in Australia is that we can make no difference to the world’s ability to tackle the climate crisis. Yet the last three decades of Australian environmental diplomacy demonstrate that when we want to make a difference, we can.

A turning point is needed to put the fight against climate change at the centre of our foreign policy, and to galvanise our industry and communities to forge a better way forward. Anthony Albanese has promised to seek to host the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s annual Conference of the Parties (COP) in partnership with Pacific Island countries. This initiative, if approached correctly, could prove to be the turning point Australia needs.

THE PROPOSAL: Australia should seek to host the COP summit in 2025, which will be a critical year for global climate diplomacy.

The 2025 conference is the next five-yearly milestone under the Paris Agreement when all countries are required to ratchet up their national ambition, including through outlining specific plans to reduce emissions by 2035. It will be the most important climate gathering since COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 and COP15, where the Paris Agreement was adopted. This would be the largest diplomatic event ever held in Australia – its planning and execution offer a range of opportunities for Australia to interact and improve relations with other states.

Practically, partnering with the Pacific would mean that many of the dozens of smaller preparatory meetings could be held in the region, including the largest “Pre-COP” meeting, held a month beforehand. Papua New Guinea would be the obvious candidate to host the Pre-COP, given that Fiji presided over the COP itself (in Bonn) in 2017.

Ordinarily, the hosting of COPs rotates between the five UN regions. The COP in 2025 would have been on track to be hosted by the Western European and Others Group, of which Australia is a part. However, the Latin American and Caribbean Group (known as ‘GRULAC’) may also now have a claim to the gathering due to the one-year delay of COP26 caused by COVID-19. Expressing an early interest and, more importantly, consulting with GRULAC will be key, including with Costa Rica, which lost out on hosting the summit during the last GRULAC rotation.

Beyond the technical negotiations and political showmanship, COPs in recent years have become large industry trade fairs. As was the case at the summits in Glasgow and Paris, we could expect 40,000 delegates to attend the main two-week conference. This would likely yield a $100-million economic windfall, helping to offset a cost admittedly several times higher than that (APEC in Sydney in 2007 cost around $450 million in today’s money). Due to the size of the event, only Melbourne and Sydney (and possibly Brisbane or Perth) would have capacity to host.

The government would also need to decide who would play the all-important and highly visible role of COP President. Often this is a member of cabinet (either the foreign minister or climate minister), but at times it has been a standalone ministerial role, given the huge workload and travel involved in the lead-up to build international consensus. It is important that the incumbent does not change once appointed, as so much becomes invested in their personal relationships.

WHY IT WILL WORK: History has shown that a strong COP presidency is essential for raising international climate ambition. French and British diplomacy were crucial for securing the outcomes they did. Australia is well placed as a G20 economy and middle power to do the same.

Labor has suggested it wants to host COP29 in 2024. Hosting in 2024 risks pushing Eastern Europe (of whom only coal-thirsty Poland usually puts up its hand to host) into the all-important 2025 presidency. While hosting in 2025 means Australia would risk holding the COP six months after a federal election, that is not an insurmountable concern (and may be helpful politically), as Australia’s campaign for a UN Security Council seat in 2013/14 showed: the Coalition originally opposed the bid, but then embraced it once they formed government. This might, however, be an argument to designate someone as COP President with strong bona fides on both sides of politics.

But the biggest opportunity for Australia is to use the COP to reinvent its approach to climate change, at home and abroad.

If Australia can secure additional climate commitments by the rest of the world, it makes it politically easier for any Australian government to do more. Australia has often pegged its climate target to that of others, including the United States. The Biden administration, with its pledge to cut emissions by 50 to 52 per cent on 2005 levels by 2030, compared to the Albanese government’s target of 43 per cent, will keep up the pressure on Australia to do more, especially with its 2035 target, which must be tabled by the 2025 summit. Some scientists have said Australia’s 2035 target will need to be closer to a 67 per cent cut, which would represent a big step up. While the government is unlikely to revisit the 2030 target before 2025, hosting a major COP would pressure it to at least send a signal this target is merely a floor and not a ceiling.

Domestically, hosting the 2025 COP would provide a huge opportunity for Australians to see the breadth and benefits of climate action taking place around the world. It would also encourage greater action by our industries, businesses, cities and communities, just as it has for other host countries. Glasgow’s hosting of COP26 helped the city council secure a new Green Deal, and Paris adopted a new Adaptation Plan just prior to COP21. These benefits are not short-lived. There is often an afterglow that lingers for years and leads to the development of new accountability mechanisms to ensure plans are delivered.

Finally, hosting the 2025 COP might help Australia put climate change at the centre of its foreign policy in the same way the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union and others have. DFAT could be forced to take an all-of-department approach to the issue – including considering carbon tariffs and prioritising climate outcomes in our trade agreements, and focusing our aid spending even more significantly on adaptation and mitigation measures. This shift, alone, would represent a profound legacy for Australian foreign policymaking.