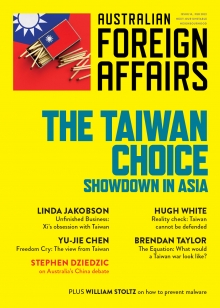

This extract is featured in Australian Foreign Affairs 14: The Taiwan Choice.

To read the full issue, log in, subscribe or buy the issue.

A full-blown conflict over Taiwan could make living through the COVID-19 pandemic seem like a cakewalk. It would very likely be the most devastating war in history, drawing the world’s major powers into their first nuclear exchange. Hundreds of millions could perish, both from the fighting itself and from the sickening after-effects of radiation. Even a limited nuclear conflict would be an environmental nightmare, with soot from incinerated cities shutting out the sun’s rays, depleting food supplies and plunging the planet into a prolonged famine. Life for Australians would be forever changed. Such a catastrophe looms closer than we think. If it eventuates, those left behind after Asia’s atomic mushroom clouds have settled will wish that we had fought with every fibre of our being to prevent it.

As China’s wealth and power have grown, so too have its military options for conquering Taiwan. Indeed, the lack of such options prompted Beijing’s massive military modernisation, which began right after the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1995–96. During that crisis, the United States forced Beijing to back down by dispatching two aircraft carrier battle groups to waters close to Taiwan. This was, at the time, the largest US naval deployment to Asia since the Vietnam War. China’s leaders vowed to never again suffer such humiliation.

China now has a range of ways to attack Taiwan. The quickest and dirtiest option is a missile strike, using the 2000-plus short- and medium-range missiles currently trained on the island. Alternatively, China could try strangling Taiwan’s 23 million people into submission by blockading food and fuel supplies. The island imports 80–90 per cent of its food and close to 100 per cent of its oil. Either option could be complemented by industrial-scale cyberwarfare, plunging one of the most interconnected societies on Earth into darkness and causing widespread panic and confusion.

The most ambitious and challenging military option is a full-scale amphibious assault. An estimated 1 to 2 million People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops would need to be ferried across the Taiwan Strait in a massive armada of military and civilian ships. This turbulent body of water – 128 kilometres at its narrowest point and 410 kilometres at its widest – is notorious for its strong currents, dense fog and inclement weather. This means that such an invasion would most likely occur either between late March and the end of April, or from late September to the end of October, when the waters are at their calmest. Moreover, the natural obstacles confronting China’s invading force are not only maritime. Taiwan’s rugged east coast consists of steep cliffs that shoot straight out of the sea, while its western flank is lined with dense mudflats that are not conducive to troop landings. Nonetheless, as the mainland’s amphibious lift capabilities continue to expand, China’s option to invade becomes increasingly viable.

However, because this would be the largest and riskiest amphibious landing operation in history, many commentators maintain that China’s strongman leader, Xi Jinping, will most likely take a graduated approach to conflict. He might start with a missile strike or cyberattack, for instance, testing and hoping to bend the will of the Taiwanese people. Should that fail, Xi could tighten the screws with a blockade. If Taiwanese resistance continued, Xi might then – and only then – issue the order to invade.

This interpretation aligns with the ancient Chinese strategy of “winning without fighting”. Most recently, Beijing has successfully employed this approach in the South China Sea, using a mix of so-called “grey zone” tactics – such as deploying large fishing fleets known as “maritime militia” to occupy disputed areas – that are short of military force but which chip away at the status quo to create new facts on the ground. Applying this template limits the risk of Beijing’s worst nightmare: US military intervention in support of Taiwan. Would Washington risk nuclear war and the possible loss of major American cities in response to a Chinese cyberattack against the island? Would US president Joe Biden really order the US Navy to fire upon a defenceless swarm of Chinese fishing vessels supporting a blockade?

Escalation and miscalculation

This conventional wisdom that China will likely attack Taiwan incrementally recalls Herman Kahn’s famous “escalation ladder”. Kahn, an eccentric American Cold War strategist who is rumoured to have inspired Stanley Kubrick’s satirical character Dr Strangelove, believed that all types of conflict – even nuclear – could ultimately be managed and controlled. His 44-rung escalation ladder sought to model the steps that leaders might take in a real-world crisis. It tried to capture the growing dangers of antagonists ascending higher and the crisis deepening, along with the choices available at each step to climb down and avert Armageddon.

But times and technologies have changed since the height of the Cold War. In a Taiwan conflict, escalation will be neither linear nor predictable. Many of the traditional distinctions, or so-called “firebreaks”, between conventional and nuclear weapons are increasingly blurred. During the Cold War, for instance, the systems that the United States used to warn of a Soviet nuclear strike were located separately, either in space or at remote geographic locations, making them difficult to target. Today, they are integrated with conventional situational awareness and strategic warning systems. Likewise, many of Beijing’s newer missiles – such as the Dongfeng 26 (DF-26) ballistic missile, known as the “carrier killer” for its capacity to target US aircraft carriers up to 4000 kilometres away – are “dual use”, meaning they can carry either a conventional or a nuclear payload.

Inspired by a combination of theoretical physics and science fiction, the American analyst Rebecca Hersman recently observed that Kahn’s escalation ladder has been usurped by what she terms “wormhole escalation”. Wormholes, as physicists including Albert Einstein have long theorised, are bridges or shortcuts between two different points in space-time. Hersman has applied this concept to conflict situations to illustrate how contemporary crises can escalate far more rapidly and unpredictably than Kahn’s well-worn metaphor anticipates. As she explained, such crises are risky and precarious – they do not progress “stepwise” because they have no “clear thresholds between behavior that would elicit a conventional or nuclear response”.

Given the unimaginable consequences, a nuclear conflict over Taiwan is far more likely to be the product of accident rather than design. It could be triggered by something as simple as an unintended collision of Chinese and Taiwanese fighters flying over the Taiwan Strait, or by a stand-off between US and Chinese ships operating in the waters below, where an exchange of fire results in one of the vessels foundering. From there, events could easily spiral out of control.

This is hardly the stuff of fiction. Chinese incursions into the waters and skies around Taiwan have ramped up substantially in recent years. Over four days in early October 2021, during China’s National Day celebrations, Beijing sent a record 149 aircraft into Taiwan’s so-called Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ), including its nuclear-capable H-6 bombers. Unlike in the past, where Taiwanese fighter aircraft typically monitored such encroachments from a distance, the island’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, has pledged to “forcibly expel” them if they transgress the Taiwan Strait’s median line, the unofficial maritime boundary that separated China and Taiwan for two decades before Beijing summarily dismissed its existence in September 2020. During that same month, Taiwan’s air force reportedly outmanoeuvred and drove a Chinese fighter out of the island’s ADIZ.

Such a crisis could also be sparked by human error. On 1 July 2016, for instance, a Taiwanese navy vessel accidentally fired an anti-shipping missile in China’s direction. The missile flew for approximately 120 kilometres before striking a Taiwanese fishing boat near Taiwan’s Penghu Islands, killing its captain and injuring three of its crew. But what if such an incident had occurred five years later, in the nationalistically charged atmosphere of the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary celebrations? And what if the missile had hit a Chinese fishing boat, a PLA Navy vessel or, worse still, reached the mainland? Could the resultant crisis have been contained?

Cooler heads might have still prevailed. Yet in any future crisis over Taiwan where the US military becomes involved, the risks of “wormhole escalation” cannot be underestimated. As soon as the shooting starts, significant “first mover” advantages will be available to both sides. The reason is simple. Modern militaries rely on a sophisticated network of radars, sonars and satellites to track an opponent’s movements. Such systems are vulnerable and difficult to defend. Taking them out is tremendously provocative, but confers decisive advantages by essentially blinding an opponent.

The temptation to pull off such a risky military manoeuvre may ultimately prove irresistible for Xi in the heat of conflict. Despite the considerable benefits conferred by geography – the island of Taiwan is 11,000 kilometres away from the continental United States – China remains well behind America in some key areas of militarily capability. A June 2021 report from the highly respected International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), for instance, estimates that China’s cyber capabilities – regarded by some analysts as the sine qua non of modern warfare – are at least a decade behind those of the US.

Likewise, China’s nuclear capabilities remain minuscule compared to America’s. China has 350 nuclear warheads; America has 3800. China also has only six submarines – the so-called Type 094 Jin-class nuclear-powered, ballistic missile-carrying submarine (SSBN) – that can deliver a nuclear strike. Such asymmetries mean that Beijing lacks what is called a secure “second strike” capability – the means to hit back at an opponent even after they have unleashed a devastating nuclear attack.

Xi is working assiduously to address this imbalance. In mid-2021, three freshly built fields of nuclear launch silos were discovered in north-central China by US-based analysts using commercial satellite imagery. The Pentagon estimates that China’s nuclear arsenal will swell to 1000 warheads by 2030. Construction of China’s next-generation SSBN (the Type 96 class) is also underway, along with a new kind of long-range, submarine-launched ballistic missile known as the JL-3. But such developments take time, as shown by Australia’s difficulties in deciding its next generation of submarine. Until these advancements come online, China’s nuclear vulnerabilities will encourage Beijing to embrace a “use them or lose them” mentality in a Taiwan conflict, reinforcing the risks of wormhole escalation.

This is a 1698 word extract of a 4664 word essay by Brendan Taylor. Get your copy of AFA14: The Taiwan Choice to read the full article, along with contributions from Hugh White, Linda Jakobson and Yu-Jie Chen.